The development of the electric automobile v/ill owe more to innovative solar and aeronautical engineering and advanced satellite and radar technology than to traditional automotive design and construction. The electric car will have no engine, exhaust system, transmission, muffler, radiator, or spark plugs. It will require neither tune- ups nor gasoline.

Background

In 1908 Henry Ford began production of the Model T automobile. Based on his original Model A design first manufactured in 1903, the Model T took five years to develop. Its creation inaugurated what we know today as the mass production assembly line. This revolutionary idea was based on the concept of simply assembling interchangeable component parts. Prior to this time, coaches and buggies had been hand-built in small numbers by specialized craftspeople who rarely duplicated any particular unit. Ford’s innovative design reduced the number of parts needed as well as the number of skilled fitters who had always formed the bulk of the assembly operation, giving Ford a tremendous advantage over his competition.

Ford’s first venture into automobile assembly with the Model A involved setting up assembly stands on which the whole vehicle was built, usually by a single assembler who fit an entire section of the car together in one place. This person performed the same activity over and over at his stationary assembly stand. To provide for more efficiency, Ford had parts delivered as needed to each work station. In this way each assembly fitter took about 8.5 hours to complete his assembly task. By the time the Model T was being developed Ford had decided to use multiple assembly stands with assemblers moving from stand to stand, each performing a specific function. This process reduced the assembly time for each fitter from 8.5 hours to a mere 2.5 minutes by rendering each worker completely familiar with a specific task.

Ford soon recognized that walking from stand to stand wasted time and created jam- ups in the production process as faster workers overtook slower ones. In Detroit in 1913, he solved this problem by introducing the first moving assembly line, a conveyor that moved the vehicle past a stationary assembler. By eliminating the need for workers to move between stations, Ford cut the assembly task for each worker from 2.5 minutes to just under 2 minutes; the moving assembly conveyor could now pace the stationary worker. The first conveyor line consisted of metal strips to which the vehicle’s wheels were attached. The metal strips were attached to a belt that rolled the length of the factory and then, beneath the floor, returned to the beginning area. This reduction in the amount of human effort required to assemble an automobile caught the attention of automobile assemblers throughout the world. Ford’s mass production drove the automobile industry for nearly five decades and was eventually adopted by almost every other industrial manufacturer. Although technological advancements have enabled many improvements to modern day automobile assembly operations, the basic concept of stationary workers installing parts on a vehicle as it passes their work stations has not changed drastically over the years.

Raw Materials

Although the bulk of an automobile is virgin steel, petroleum-based products (plastics and vinyls) have come to represent an increasingly large percentage of automotive components. The light-weight materials derived from petroleum have helped to lighten some models by as much as thirty percent. As the price of fossil fuels continues to rise, the preference for lighter, more fuel efficient vehicles will become more pronounced.

Design

Introducing a new model of automobile generally takes three to five years from inception to assembly. Ideas for new models are developed to respond to unmet pubic needs and preferences. Trying to predict what the public will want to drive in five years is no small feat, yet automobile companies have successfully designed automobiles that fit public tastes. With the help of computer-aided design equipment, designers develop basic concept drawings that help them visualize the proposed vehicle’s appearance. Based on this simulation, they then construct clay models that can be studied by styling experts familiar with what the public is likely to accept. Aerodynamic engineers also review the models, studying air-flow parameters and doing feasibility studies on crash tests. Only after all models have been reviewed and accepted are tool designers permitted to begin building the tools that will manufacture the component parts of the new model.

The Manufacturing Process

Components

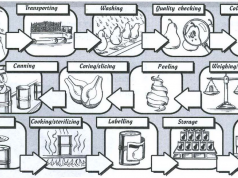

I The automobile assembly plant represents only the final phase in the process of manufacturing an automobile, for it is here that the components supplied by more than 4.000 outside suppliers, including company-owned parts suppliers, are brought together for assembly, usually by truck or railroad. Those parts that will be used in the chassis are delivered to one area, while those that will comprise the body are unloaded at another.

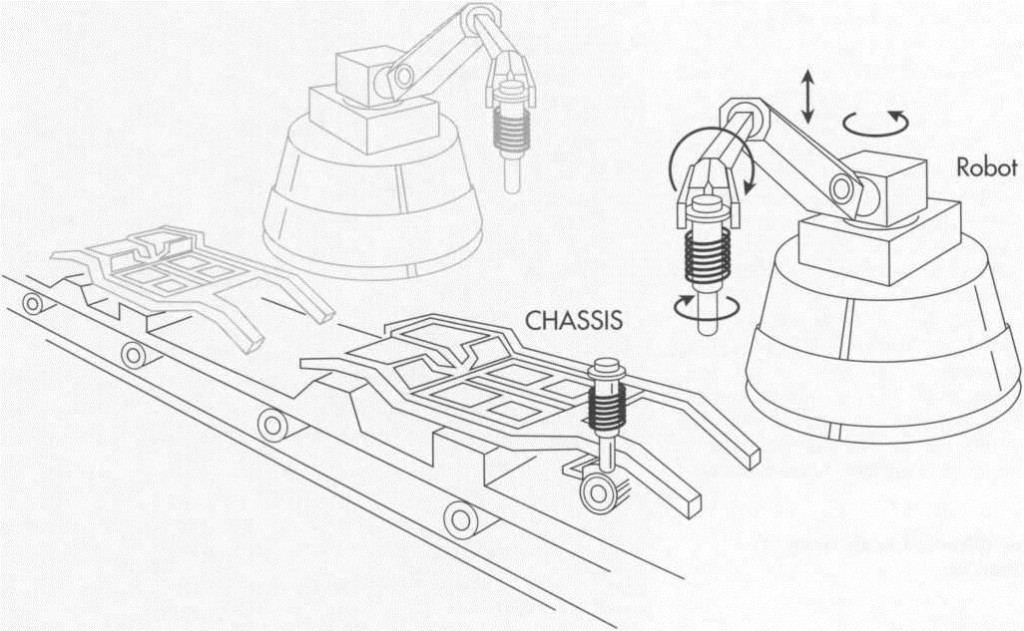

Chassis

2 The typical car or truck is constructed from the ground up (and out). The frame forms the base on which the body rests and from which all subsequent assembly components follow. The frame is placed on the assembly line and clamped to the conveyer to prevent shifting as it moves down the line. From here the automobile frame moves to component assembly areas where complete front and rear suspensions, gas tanks, rear axles and drive shafts, gear boxes, steering box components, wheel drums, and braking systems are sequentially installed

The automobile, (or decades rhe quintessential American industrial produd, did not have its origins in the United States In 1860, Etienne Lenoir, a Belgion mechanic, introduced rcn internal combustion engine thot proved useful as a source ol stationary power In 1878, Nicholas Otto, a German manufacturer, developed his four stroke “explosion ‘ engine. By 1885, one of his engineer», Gottlieb Daimler, wa! building the first of foui experimental vehicles powered by a modified Otto internal combustion engine. Also in 1885, another Germon manufacturer, Carl Benz, introduced a three wheeled, self-propelled vehicle In 1887, the Benz became the first automobile offered for sale to the public. By I 895, automotive technology was dominated by the French, led by Emile Lavassar Lavassor developed the basic mechanical nrrangemenl of the car, placing the engine in the front of the chassis, with the cronkshaft perpendicular to the axles. In 1896, the Doryea Motor Wagon became the first production motor vehicle the United States In that some yeoi. Henry Ford demonstrated his first expermental vehicle , the Quadricycle By 1908, when the Ford MotorCompany introduced the Model T, the United States had dozens of automobile manufacturers. The Model T quickly become the standard by which other cars were measured,• ten yenrs later half of all cars on the road were Model Ts It hod a simple foui-cylinder twenty-horvepower engine and a planetary transmission giving two gears forward and one backward. It was sturdy, had high road cleoionce to negotiate the rutted roads of the day, and was easyto operate and maintain

William S. Pretz&r

3 An off-line operation at this stage of production mates the vehicle’s engine with its transmission. Workers use robotic arms to install these heavy components inside the engine compartment of the frame. After the engine and transmission are installed, a worker attaches the radiator, and another bolts it into place. Because of the nature of these heavy component parts, articulating robots perform all of the lift and carry operations while assemblers using pneumatic wrenches bolt component pieces in place. Careful ergonomic studies of every assembly task have provided assembly workers with the safest and most efficient tools available.

(On automobile assembly lines, much of the work is now done by robots rather than humans. In tfie first stages of automobile manufacture, robots weld the floor pan pieces together and assist workers in placing components such as the suspension onto the chassis.)

Body

4 Generally, the floor pan is the largest body component to which a multitude of panels and braces will subsequently be either welded or bolted. As it moves down the assembly line, held in place by clamping fixtures, the shell of the vehicle is built. First, the left and right quarter panels are robotically disengaged from pre-staged shipping containers and placed onto the floor pan, where they are stabilized with positioning fixtures and welded.

5 The front and rear door pillars, roof, and body side panels are assembled in the same fashion. The shell of the automobile assembled in this section of the process lends itself to the use of robots because articulating arms can easily introduce various component braces and panels to the floor pan and perform a high number of weld operations in atime frame and with a degree of accuracy no human workers could ever approach. Robots can pick and load 200-pound (90.8 kilograms) roof panels and place them precisely in the proper weld position with tolerance variations held to within .001 of an inch.

Moreover, robots can also tolerate the smoke, weld flashes, and gases created during this phase of production.

The body is built up on a separate assembly line from the chassis. Robots once again perform most of the welding on the various panels, but human workers are necessary to bolt the parts together. During welding, component pieces are held securely in a jig while welding operations are performed. Once the body shell is complete, it is attached to an overhead conveyor for the painting process. The multi-step painting process entails inspection, cleaning, undercoat (electrostatically applied) dipping, drying, top-coat spraying, and baking.

As the body moves from the isolated weld area of the assembly line, subsequent body components including fully assembled doors, deck lids, hood panel, fenders, trunk lid, and bumper reinforcements are installed. Although robots help workers place these components onto the body shell, the workers provide the proper fit for most of the bolt-on functional parts using pneumatically assisted tools.

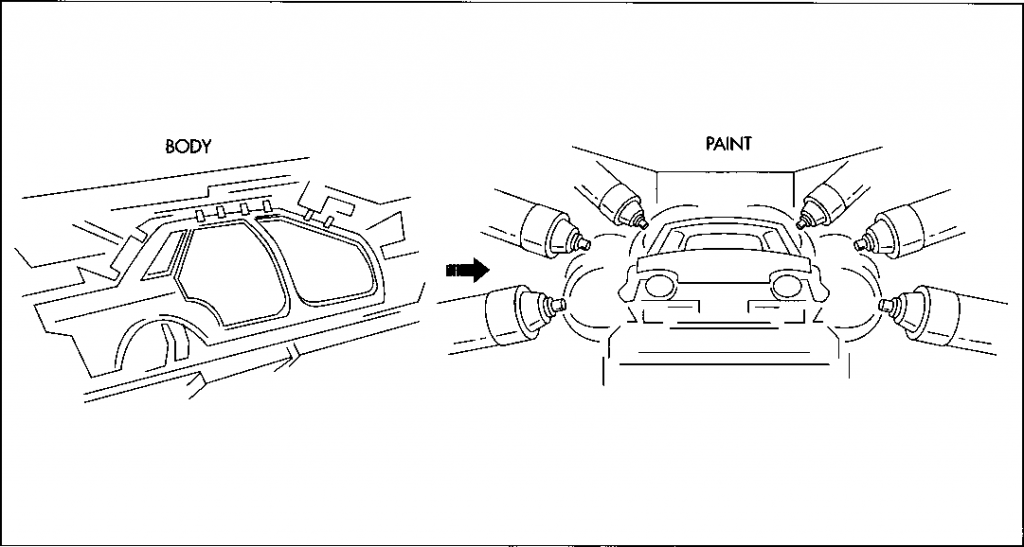

Paint

7 Prior to painting, the body must pass through a rigorous inspection process, the body in white operation. The shell of the vehicle passes through a brightly lit white room where it is fully wiped down by visual inspectors using cloths soaked in hi-light oil. Under the lights, this oil allows inspectors to see any defects in the sheet metal body panels. Dings, dents, and any other defects are repaired right on the line by skilled body repairmen. After the shell has been fully inspected and repaired, the assembly conveyor carries it through a cleaning station where it is immersed and cleaned of all residual oil, dirt, and contaminants.

8 As the shell exits the cleaning station it goes through a drying booth and then through an undercoat dip—an electrostatically charged bath of undercoat paint (called the E-coat) that covers every nook and cranny of the body shell, both inside and out, with primer. This coat acts as a substrate surface to which the top coat of colored paint adheres.

9 After the E-coat bath, the shell is again dried in a booth as it proceeds on to the final paint operation. In most automobile assembly plants today, vehicle bodies are spray-painted by robots that have been programmed to apply the exact amounts of paint to just the right areas for just the right length of time. Considerable research and programming has gone into the dynamics of robotic painting in order to ensure the fine “wet” finishes we have come to expect. Our robotic painters have come a long way since Ford’s first Model Ts, which were painted by hand with a brush. Once the shell has been fully covered with a base coat of color paint and a clear top coat, the conveyor transfers the bodies through baking ovens where the paint is cured at temperatures exceeding 275 degrees Fahrenheit (135 degrees Celsius).

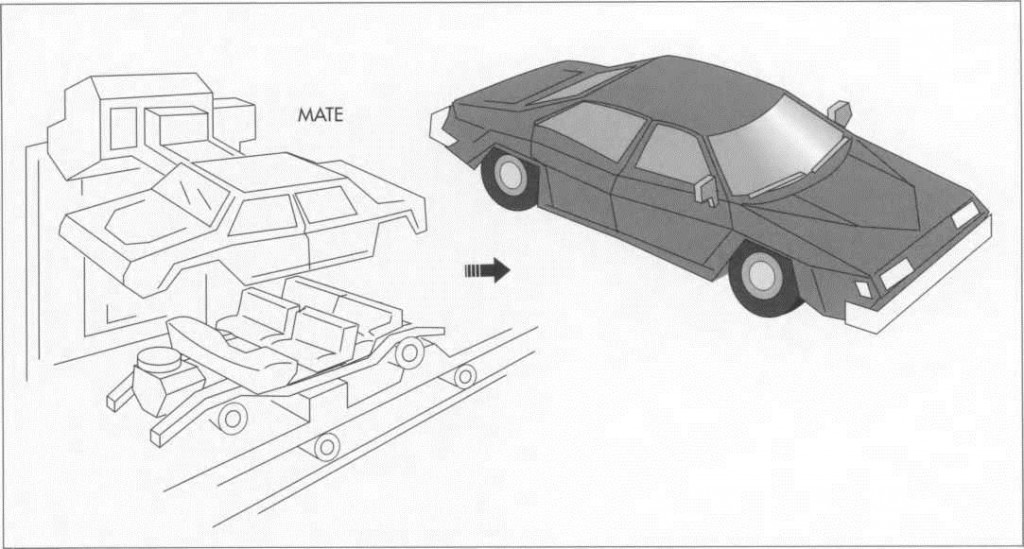

(The body and chassis assemblies are mated near the end of the production process. Robotic arms lift the body shell onto the chassis frame, where human workers then bolt the two together. After final components are installed, the vehicle is driven off the assembly line to a quality checkpoint.)

After the shell leaves the paint area it is ready for interior assembly.

Interior assembly

1 1 The painted shell proceeds through the I I interior assembly area where workers assemble all of the instrumentation and wiring systems, dash panels, interior lights, seats, door and trim panels, headliners, radios, speakers, all glass except the auto mobile windshield, steering column and wheel, body weather strips, vinyl tops, brake and gas pedals, carpeting, and front and rear bumper fascias.

1 O Next, robots equipped with suction

I cups remove the windshield from a shipping container, apply a bead of urethane sealer to the perimeter of the glass, and then place it into the body windshield frame. Robots also pick seats and trim panels and transport them to the vehicle for the ease and efficiency of the assembly operator. After passing through this section the shell is given a water test to ensure the proper fit of door panels, glass, and weathers tripping. It is now ready to mate with the chassis

Mate

13

The chassis assembly conveyor and the body shell conveyor meet at this stage of production. As the chassis passes the body conveyor the shell is robotically lifted from its conveyor fixtures and placed onto the car frame. Assembly workers, some at ground level and some in work pits beneath the conveyor, bolt the car body to the frame. Once the mating takes place the automobile proceeds down the line to receive final trim components, battery, tires, anti-freeze, and gasoline.

The vehicle can now be started. From here it is driven to a checkpoint off the line, where its engine is audited, its lights and horn checked, its tires balanced, and its charging system examined. Any defects discovered at this stage require that the car be taken to a central repair area, usually located near the end of the line. A crew of skilled trouble-shooters at this stage analyze and repair all problems. When the vehicle passes final audit it is given a price label and driven to a staging lot where it will await shipment to its destination.

Quality

All of the components that go into the automobile are produced at other sites. This means the thousands of component pieces that comprise the car must be manufactured, tested, packaged, and shipped to the assembly plants, often on the same day they will be used. This requires no small amount of planning. To accomplish it, most automobile manufacturers require outside parts vendors to subject their component parts to rigorous testing and inspection audits similar to those used by the assembly plants. In this way the assembly plants can anticipate that the products arriving at their receiving docks are Statistical Process Control (SPC) approved and free from defects.

Once the component parts of the automobile begin to be assembled at the automotive factory, production control specialists can follow the progress of each embryonic automobile by means of its Vehicle Identification Number (VIN), assigned at the start of the production line. In many of the more advanced assembly plants a small radio frequency transponder is attached to the chassis and floor pan. This sending unit carries the VIN information and monitors its progress along the assembly process. Knowing what operations the vehicle has been through, where it is going, and when it should arrive at the next assembly station gives production management personnel the ability to electronically control the manufacturing sequence. Throughout the assembly process quality audit stations keep track of vital information concerning the integrity of various functional components of the vehicle.

This idea comes from a change in quality control ideology over the years. Formerly, quality control was seen as a final inspection process that sought to discover defects only after the vehicle was built. In contrast, today quality is seen as a process built right into the design of the vehicle as well as the assembly process. In this way assembly operators can stop the conveyor if workers find a defect. Corrections can then be made, or supplies checked to determine whether an entire batch of components is bad. Vehicle recalls are costly and manufacturers do everything possible to ensure the integrity of their product before it is shipped to the customer. After the vehicle is assembled a validation process is conducted at the end of the assembly line to verify quality audits from the various inspection points throughout the assembly process. This final audit tests for properly fitting panels; dynamics; squeaks and rattles; functioning electrical components; and engine, chassis, and wheel alignment. In many assembly plants vehicles are periodically pulled from the audit line and given full functional tests. All efforts today are put forth to ensure that quality and reliability are built into the assembled product.

The Future

The development of the electric automobile will owe more to innovative solar and aeronautical engineering and advanced satellite and radar technology than to traditional automotive design and construction. The electric car has no engine, exhaust system, transmission, muffler, radiator, or spark plugs. It will require neither tune-ups nor—truly revolutionary—gasoline. Instead, its power will come from alternating current (AC) electric motors with a brushless design capable of spinning up to 20,000 revolutions/minute. Batteries to power these motors will come from high performance cells capable of generating more than 100 kilowatts of power. And, unlike the lead-acid batteries of the past and present, future batteries will be environmentally safe and recyclable. Integral to the braking system of the vehicle will be a power inverter that converts direct current electricity back into the battery pack system once the accelerator is let off, thus acting as a generator to the battery system even as the car is driven long into the future.

The growth of automobile use and the increasing resistance to road building have made our highway systems both congested and obsolete. But new electronic vehicle technologies that permit cars to navigate around the congestion and even drive themselves may soon become possible. Turning over the operation of our automobiles to computers would mean they would gather information from the roadway about congestion and find the fastest route to their instructed destination, thus making better use of limited highway space. The advent of the electric car will come because of a rare convergence of circumstance and ability. Growing intolerance for pollution combined with extraordinary technological advancements will change the global transportation paradigm that will carry us into the twenty- first century.

Where To Learn More

Books

Abernathy, William. The Productivity Dilemma: Roadblock to Innovation in the Automobile Industry. Johns Hopkins University Press, 1978.

Gear Design, Manufacturing & Inspection Manual. Society of Manufacturing Engineers, Inc., 1990.

Hounshell, David. From the American System to Mass Production. Johns Hopkins University Press, 1984.

Lamming, Richard. Beyond Partnership: Strategies for Innovation á Lean Supply. Prentice Hall, 1993.

Making the Car. Motor Vehicle Manufac¬turers Association of the United States, 1987.

Mortimer, J., ed. Advanced Manufacturing in the Automotive Industry. Springer-Verlag New York, Inc., 1987.

Mortimer, John. Advanced Manufacturing in the Automotive Industry. Air Science Co., 1986.

Nevins, Allen and Frank E. Hill. Ford: The Times, The Man, The Company. Scribners, 1954.

Seiffert, Ulrich. Automobile Technology of the Future. Society of Automotive En¬gineers, Inc., 1991.

Sloan, Alfred P. My Years with General Motors. Doubleday, 1963.

Periodicals

“The Secrets of the Production Line,” The Economist. October 17, 1992, p. S5.