Background

Bulletproof vests are modern light armor specifically designed to protect the wearer’s vital organs from injury caused by firearm projectiles. To many protective armor manufacturers and wearers, the term “bulletproof vest” is a misnomer. Because the wearer is not totally safe from the impact of a bullet, the preferred term for the article is “bullet resistant vest.”

Over the centuries, different cultures developed body armor for use during combat. My cenaeans of the sixteenth century B.C. and Persians and Greeks around the fifth century B.C. used up to fourteen layers of linen, while Micronesian inhabitants of the Gilbert and Ellice Islands used woven coconut palm fiber until the nineteenth century. Elsewhere, armor was made from the hides of animals: the Chinese—as early as the eleventh century B.C.—wore rhinoceros skin in five to seven layers, and the Shoshone Indians of North America also developed jackets of several layers of hide that were glued or sewn together. Quilted armor was available in Central America before Cortes, in England in the seventeenth century, and in India until the nineteenth century.

Mail armor comprised linked rings or wires of iron, steel, or brass and was developed as early as 400 B.C. near the Ukrainian city of Kiev. The Roman Empire utilized mail shirts, which remained the main piece of armor in Europe until the fourteenth century. Japan, India, Persia, Sudan, and Nigeria also developed mail armor. Scale armor, overlapping scales of metal, horn, bone, leather, or scales from an appropriately scaled animal (such as the scaly anteater), was used throughout the Eastern Hemisphere from about 1600 B.C. until modem times. Sometimes, as in China, the scales were sewn into cloth pockets.

Brigandine armor—sleeveless, quilted jackets—consisted of small rectangular iron or steel plates riveted onto leather strips that overlapped like roof tiles. The result was a relatively light, flexible jacket. (Earlier coats of plates in the twelfth-century Europe were heavier and more complete. These led to the familiar full-plate suit of armor of the 1500s and 1600s.) Many consider brigandine armor the forerunner of today’s bulletproof vests. The Chinese and Koreans had similar armor around a.d. 700, and during the fourteenth century in Europe, it was the common form of body armor. One piece of breastplate within a cover became the norm after 1360, and short brigandine coats with plates that were tied into place prevailed in Europe until 1600.

With the introduction of firearms, armor crafts workers at first tried to compensate by reinforcing the cuirass, or torso cover, with thicker steel plates and a second heavy plate over the breastplate, providing some protection from guns. Usually, though, cumbersome armor was abandoned wherever firearms came into military use.

Experimental inquiry into effective armor against gunfire continued, most notably during the American Civil War, World War I, and World War II, but it was not until the plastics revolution of the 1940s that effective bulletproof vests became available to law enforcers, military personnel, and others. The vests of the time were made of ballistic nylon and supplemented by plates of fiberglass, steel, ceramic, titanium, Doron, and

To many protective armor manufacturers and wearers, the term “bulletproof vest” is a misnomer. Because the wearer is not totally safe from the impact of a bullet, the preferred term for the article is “bullet resistant vest.”

Ballistic nylon was the standard cloth used for bulletproof vests until the 1970s. In 1965, Stephanie Kwolek, a chemist at Du Pont, invented Kevlar, trademark for poly- paraphenylene terephthalamide, a liquid polymer that can be spun into aramid fiber and woven into cloth. Originally, Kevlar was developed for use in tires, and later for such diverse products as ropes, gaskets, and various parts for planes and boats. In 1971, Lester Shubin of the National Institute of Law Enforcement and Criminal Justice advocated its use to replace bulky ballistic nylon in bulletproof vests. Kevlar has been the standard material since. In 1989, the Allied Signal Company developed a competitor for Kevlar and called it Spectra. Originally used for sail cloth, the polyethylene fiber is now used to make lighter, yet stronger, nonwoven material for use in bulletproof vests alongside the traditional Kevlar.

Raw Materials

A bulletproof vest consists of a panel, a vest-shaped sheet of advanced plastics polymers that is composed of many layers of either Kevlar, Spectra Shield, or, in other countries, Twaron (similar to Kevlar) or Bynema (similar to Spectra). The layers of woven Kevlar are sewn together using Kevlar thread, while the nonwoven Spectra Shield is coated and bonded with resins such as Kraton and then sealed between two sheets of polyethylene film.

The panel provides protection but not much comfort. It is placed inside of a fabric shell that is usually made from a polyester/cotton blend or nylon. The side of the shell facing the body is usually made more comfortable by sewing a sheet of some absorbent material such as Kumax onto it. A bulletproof vest may also have nylon padding for extra protection. For bulletproof vests intended to be worn in especially dangerous situations, built-in pouches are provided to hold plates made from either metal or ceramic bonded to fiberglass. Such vests can also provide protection in car accidents or from stabbing.

Various devices are used to strap the vests on. Sometimes the sides are connected with elastic webbing. Usually, though, they are secured with straps of either cloth or elastic, with metallic buckles or velcro closures. The Manufacturing Process Some bulletproof vests are custom-made to meet the customer’s protection needs or size. Most, however, meet standard protection regulations, have standard clothing industry sizes (such as 38 long, 32 short), and are sold in quantity.

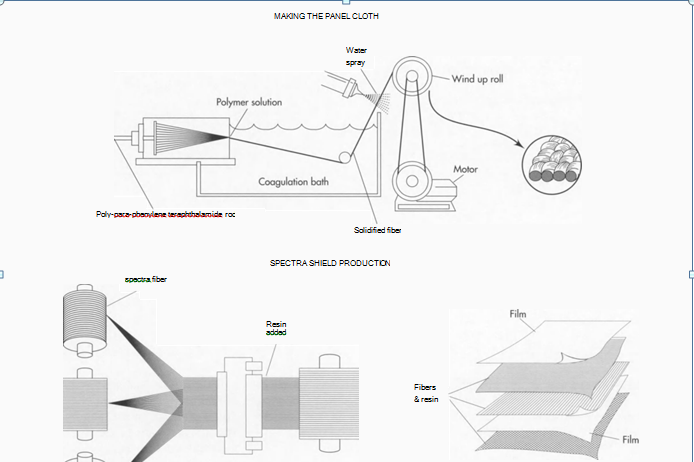

Making the panel cloth

I To make Kevlar, the polymer poly-paraphenylene terephthalamide must first be produced in the laboratory. This is done through a process known as polymerization, which involves combining molecules into long chains. The resultant crystalline liquid with polymers in the shape of rods is then extruded through a spinneret (a small metal plate full of tiny holes that looks like a shower head) to form Kevlar yarn. The Kevlar fiber then passes through a cooling bath to help it harden. After being sprayed with water, the synthetic fiber is wound onto rolls. The Kevlar manufacturer then typically sends the fiber to throw steers, who twist the yam to make it suitable for weaving. To make Kevlar cloth, the yams are woven in the simplest pattern, plain or tabby weave, which is merely the over and under pattern of threads that interlace alternatively.

2 Unlike Kevlar, the Spectra used in bulletproof vests is usually not woven. Instead, the strong polyethylene polymer fil-aments are spun into fibers that are then laid parallel to each other. Resin is used to coat the fibers, sealing them together to form a sheet of Spectra cloth. Two sheets of this cloth are then placed at right angles to one another and again bonded, forming a nonwoven fabric that is next sandwiched between two sheets of polyethylene film. The vest shape can then be cut from the material.

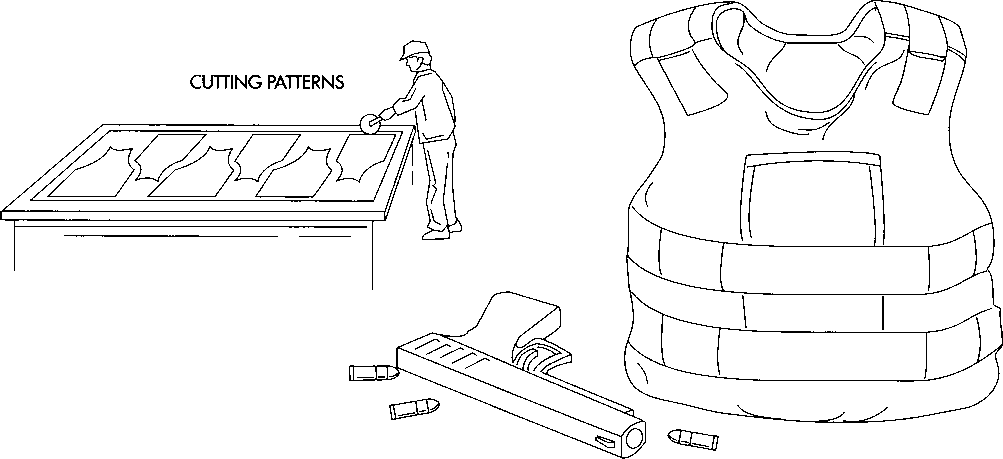

Cutting the panels

3 Kevlar cloth is sent in large rolls to the bulletproof vest manufacturer. The fabric is first unrolled onto a cutting table that must be long enough to allow several panels to be cut out at a time; sometimes it can be as long as 32.79 yards (30 meters). As many layers of the material as needed (as few as eight layers, or as many as 25, depending on the level of protection desired) are laid out on the cutting table.

4 A cut sheet, similar to pattern pieces used for home sewing, is then placed on the layers of cloth. For maximum use of the material, some manufacturers use computer graphics systems to determine the optimal placement of the cut sheets.

5 Using a hand-held machine that performs like a jigsaw except that instead of a cutting wire it has a 5.91-inch (15-centimeter) cutting wheel similar to that on the end of a pizza cutter, a worker cuts around the cut sheets to form panels, which are then placed in precise stacks.

Sewing the panels

6 While Spectra Shield generally does not require sewing, as its panels are usually just cut and stacked in layers that go into tight fitting pouches in the vest, a bulletproof vest made from Kevlar can be either quilt- stitched or box-stitched. Quilt-stitching forms small diamonds of cloth separated by stitching, whereas box stitching forms a large single box in the middle of the vest. Quilt- stitching is more labor intensive and difficult, and it provides a stiff panel that is hard to shift away from vulnerable areas. Box- stitching, on the other hand, is fast and easy and allows the free movement of the vest.

(Kevlar has long been the most widely used material in bulletproof vests. To make Kevlar, the polymer solution is first produced. The resulting liquid is then extruded from a spinneret, cooled with water, stretched on rollers, and wound into cloth. A recent competitor to Kevlar is Spectra Shield. Unlike Kevlar, Spectra Shield is not woven but rather spun into fibers that are then laid parallel to each other. The fibers are coated with resin and layered to form the cloth)

7 To sew the layers together, workers place a stencil on top of the layers and rub chalk on the exposed areas of the panel making a dotted line on the cloth. A sewer then stitches the layers together, following the pattern made by the chalk. Next, a size label is sewn onto the panel.

Finishing the vest

8 The shells for the panels are sewn together in the same factory using standard industrial sewing machines and standard sewing practices. The panels are then slipped inside the shells, and the accessories—such as the straps—are sewn on. The finished bulletproof vest is boxed and shipped to the customer.

Quality Control

Bulletproof vests undergo many of the same tests a regular piece of clothing does. The fiber manufacturer tests the fiber and yarn tensile strength, and the fabric weavers test the tensile strength of the resultant cloth. Nonwoven Spectra is also tested for tensile strength by the manufacturer. Vest manufacturers test the panel material (whether Kevlar or Spectra) for strength, and production quality control requires that trained observers inspect the vests after the panels are sewn and the vests completed.

Bulletproof vests, unlike regular clothing, must undergo stringent protection testing as required by the National Institute of Justice (NIJ). Not all bulletproof vests are alike. Some protect against lead bullets at low velocity, and some protect against full metal jacketed bullets at high velocity. Vests are classified numerically from lowest to highest protection: I, II-A, II, III-A, III, IV, and special cases (those for which the customer specifies the protection needed). Each classification specifies which type of bullet at what velocity will not penetrate the vest. While it seems logical to choose the highest- rated vests (such as III or IV), such vests are heavy, and the needs of a person wearing one might deem a lighter vest more appropriate. For police use, a general rule suggested by experts is to purchase a vest that protects against the type of firearm the officer normally carries.

The size label on a vest is very important. Not only does it include size, model, style, manufacturer’s logo, and care instructions as regular clothing does, it must also include the protection rating, lot number, date of issue, an indication of which side should face out, a serial number, a note indicating it meets NIJ approval standards, and—for type I through type III-A vests—a large warning that the vest will not protect the wearer from sharp instruments or rifle fire.

Bulletproof vests are tested both wet and dry. This is done because the fibers used to make a vest perform differently when wet. Testing (wet or dry) a vest entails wrapping it around a modeling clay dummy. A firearm of the correct type with a bullet of the correct type is then shot at a velocity suitable for the classification of the vest. Each shot should be three inches (7.6 centimeters) away from the edge of the vest and almost two inches from (five centimeters) away from previous shots. Six shots are fired, two at a 30-degree angle of incidence, and four at a O-degree angle of incidence. One shot should fall on a seam. This method of shooting forms a wide triangle of bullet holes. The vest is then turned upside down and shot the same way, this time making a narrow triangle of bullet holes. To pass the test, the vest should show no sign of penetration. That is, the clay dummy should have no holes or pieces of vest or bullet in it. Though the bullet will leave a dent, it should be no deeper than 1.7 inches (4.4 centimeters).

When a vest passes inspections, the model number is certified and the manufacturer can then make exact duplicates of the vest. After the vest has been tested, it is placed in an archive so that in the future vests with the same model number can be easily checked against the prototype.

Rigged field testing is not feasible for bulletproof vests, but in a sense, wearers (such as police officers) test them every day. Studies of wounded police officers have shown that bulletproof vests save hundreds of lives each year.

Where To Learn More

Books

Tarassuk, Leonid and Claude Blair, eds. The Complete Encyclopedia of Arms and Weapons. Simon and Schuster, 1979.

Periodicals

Anderson, Jack and Dale Van Atta. “Standoff Over Bullet-Proof Vest Standard,” Washington Post. April 9, 1990, p. B-9.

Chapnick, Howard. “The Need for Body Armor,” Popular Photography. November 1982, pp. 62+.

Faison, Seth, Jr. “Police Insist on Complete Vests,” New York Times. September 15,

1991, p. 34.

Flanagan, William G., ed. “Arms and the Man,” Forbes. July 6, 1981, p. 135.

Lappen, Alyssa A. “Step Aside, Superman,” Forbes. February 6, 1989, pp. 124-126.

—Rose Secrest