Background

Paint is a term used to describe a number of substances that consist of a pigment suspended in a liquid or paste vehicle such as oil or water. With a brush, a roller, or a spray gun, paint is applied in a thin coat to various surfaces such as wood, metal, or stone. Although its primary purpose is to protect the surface to which it is applied, paint also provides decoration.

Samples of the first known paintings, made between 20,000 and 25,000 years ago, survive in caves in France and Spain. Primitive paintings tended to depict humans and animals, and diagrams have also been found. Early artists relied on easily available natural substances to make paint, such as natural earth pigments, charcoal, berry juice, lard, blood, and milkweed sap. Later, the ancient Chinese, Egyptians, Hebrews, Greeks, and Romans used more sophisticated materials to produce paints for limited decoration, such as painting walls. Oils were used as varnishes, and pigments such as yellow and red ochres, chalk, arsenic sulfide yellow, and malachite green were mixed with binders such as gum arabic, lime, egg albumen, and beeswax.

Paint was first used as a protective coating by the Egyptians and Hebrews, who applied pitches and balsams to the exposed wood of their ships. During the Middle Ages, some inland wood also received protective coatings of paint, but due to the scarcity of paint, this practice was generally limited to store fronts and signs. Around the same time, artists began to boil resin with oil to obtain highly miscible (mixable) paints, and artists of the fifteenth century were the first to add drying oils to paint, thereby hastening evaporation. They also adopted a new solvent, linseed oil, which remained the most commonly used solvent until synthetics replaced it during the twentieth century.

In Boston around 1700, Thomas Child built the earliest American paint mill, a granite trough within which a 1.6 foot (.5 meter) granite ball rolled, grinding the pigment. The first paint patent was issued for a product that improved whitewash, a water-slaked lime often used during the early days of the United States. In 1865 D. P. Flinn obtained a patent for a water-based paint that also contained zinc oxide, potassium hydroxide, resin, milk, and linseed oil. The first commercial paint mills replaced Child’s granite ball with a buhrstone wheel, but these mills continued the practice of grinding only pigment (individual customers would then blend it with a vehicle at home). It wasn’t until 1867 that manufacturers began mixing the vehicle and the pigment for consumers.

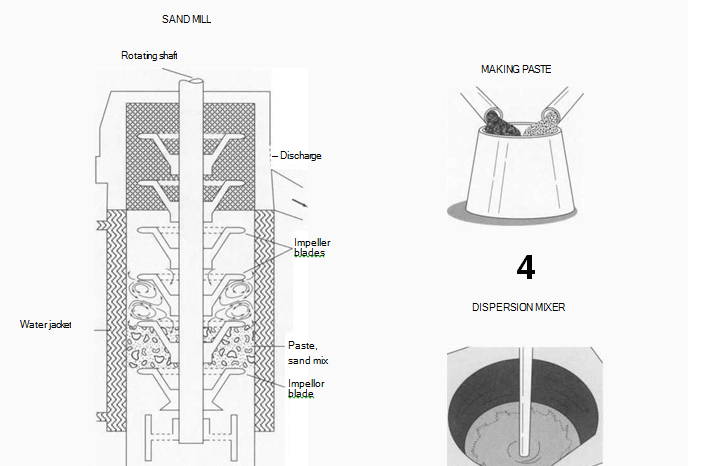

The twentieth century has seen the most changes in paint composition and manufacture. Today, synthetic pigments and stabilizers are commonly used to mass produce uniform batches of paint. New synthetic vehicles developed from polymers such as polyurethane and styrene butadene emerged during the 1940s. Alkyd resins were synthesized, and they have dominated production since. Before 1930, pigment was ground with stone mills, and these were later replaced by steel balls. Today, sand mills and high-speed dispersion mixers are used to grind easily dispersible pigments.

Perhaps the greatest paint-related advancement has been its proliferation. While some wooden houses, stores, bridges, and signs were painted as early as the eighteenth century, it wasn’t until recently that mass production rendered a wide variety of paints universally indispensable. Today, paints are used for interior and exterior house painting, boats, automobiles, planes, appliances, furniture, and many other places where protection and appeal are desired

(The first step in making paint involves mixing the pigment with resin, solvents, and additives to form a paste. If the paint is to be for industrial use, it usually is then routed into a sand mill, a large cylinder that agitates tiny particles of sand or silica to grind the pigment particles, making them smaller and dispersing them throughout the mixture. In contrast, most commercial-use paint is processed in a high-speed dispersion tank, in which a circular, toothed blade attached to a rotating shaft agitates the mixture and blends the pigment into the solvent.)

Raw Materials

A paint is composed of pigments, solvents, resins, and various additives. The pigments give the paint color; solvents make it easier to apply; resins help it dry; and additives serve as everything from fillers to antifungicidal agents. Hundreds of different pigments, both natural and synthetic, exist. The basic white pigment is titanium dioxide, selected for its excellent concealing properties, and black pigment is commonly made from carbon black. Other pigments used to make paint include iron oxide and cadmium sulfide for reds, metallic salts for yellows and oranges, and iron blue and chrome yellows for blues and greens.

Solvents are various low viscosity, volatile liquids. They include petroleum mineral spirits and aromatic solvents such as benzol, alcohols, esters, ketones, and acetone. The natural resins most commonly used are linseed, coconut, and soybean oil, while alkyds, acrylics, epoxies, and polyurethanes number among the most popular synthetic resins. Additives serve many purposes. Some, like calcium carbonate and aluminum silicate, are simply fillers that give the paint body and substance without changing its properties. Other additives produce certain desired char acteristics in paint, such as the thixotropic agents that give paint its smooth texture, driers, anti-settling agents, anti-skinning agents, defoamers, and a host of others that enable paint to cover well and last long.

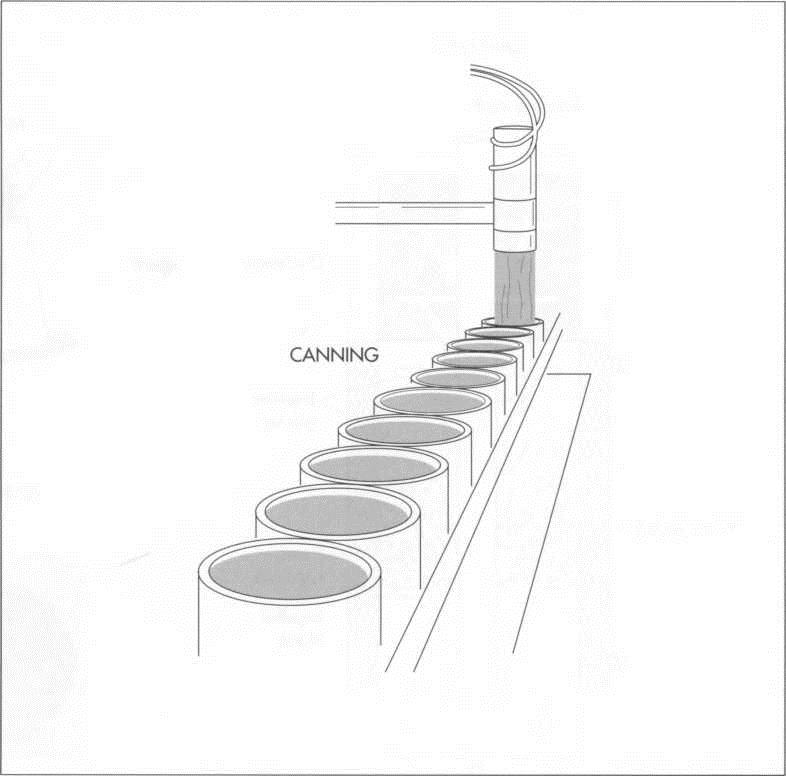

(Paint canning is a completely automated process. For the standard 8 pint paint can available to consumers, empty cans are first rolled horizontally onto labels, then set upright so that the paint can be pumped into them. One machine places lids onto the filled cans while a second machine presses on the lids to seal the cans. From wire that is fed into it from coils, a bailometer cuts and shapes the handles before hooking them into holes precut in the cans.)

Design

Paint is generally custom-made to fit the needs of industrial customers. For example, one might be especially interested in a fast- drying paint, while another might desire a paint that supplies good coverage over a long lifetime. Paint intended for the consumer can also be custom-made. Paint manufacturers provide such a wide range of colors that it is impossible to keep large quantities of each on hand. To meet a request for “aquamarine,” “canary yellow,” or “maroon,” the manufacturer will select a base that is appropriate for the deepness of color required. (Pastel paint bases will have high amounts of titanium dioxide, the white pigment, while darker tones will have less.) Then, according to a predetermined formula, the manufacturer can introduce various pigments from calibrated cylinders to obtain the proper color.

The Manufacturing Process

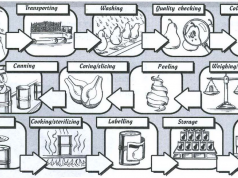

Making the paste

1 Pigment manufacturers send bags of fine grain pigments to paint plants. There, the pigment is premixed with resin (a wetting agent that assists in moistening the pigment), one or more solvents, and additives to form a paste.

Dispersing the pigment

2 The paste mixture for most industrial and some consumer paints is now routed into a sand mill, a large cylinder that agitates tiny particles of sand or silica to grind the pigment particles, making them smaller and dispersing them throughout the mixture. The mixture is then filtered to remove the sand particles.

3 Instead of being processed in sand mills, up to 90 percent of the water-based latex paints designed for use by individual homeowners are instead processed in a high-speed dispersion tank. There, the premixed paste is subjected to high-speed agitation by a circular, toothed blade attached to a rotating shaft. This process blends the pigment into the solvent.

Thinning the paste

4 Whether created by a sand mill or a dispersion tank, the paste must now be thinned to produce the final product. Transferred to large kettles, it is agitated with the proper amount of solvent for the type of paint desired.

Canning the paint

5 The finished paint product is then pumped into the canning room. For the standard 8 pint (3.78 liter) paint can available to consumers, empty cans are first rolled horizontally onto labels, then set upright so that the paint can be pumped into them. A machine places lids onto the filled cans, and a second machine presses on the lids to seal them. From wire that is fed into it from coils, a bailometer cuts and shapes the handles before hooking them into holes precut in the cans. A certain number of cans (usually four) are then boxed and stacked before being sent to the warehouse.

Quality Control

Paint manufacturers utilize an extensive array of quality control measures. The ingredients and the manufacturing process undergo stringent tests, and the finished product is checked to insure that it is of high quality. A finished paint is inspected for its density, fineness of grind, dispersion, and viscosity. Paint is then applied to a surface and studied for bleed resistance, rate of drying, and texture.

In terms of the paint’s aesthetic components, color is checked by an experienced observer and by spectral analysis to see if it matches a standard desired color. Resistance of the color to fading caused by the elements is determined by exposing a portion of a painted surface to an arc light and comparing the amount of fading to a painted surface that was not so exposed. The paint’s hiding power is measured by painting it over a black surface and a white surface. The ratio of coverage on the black surface to coverage on the white surface is then determined, with .98 being high-quality paint. Gloss is measured by determining the amount of reflected light given off a painted surface.

Tests to measure the paint’s more functional qualities include one for mar resistance, which entails scratching or abrading a dried coat of paint. Adhesion is tested by making a crosshatch, calibrated to .07 inch (2 millimeters), on a dried paint surface. A piece of tape is applied to the crosshatch, then pulled off; good paint will remain on the surface. Scrubbability is tested by a machine that rubs a soapy brush over the paint’s surface. A system also exists to rate settling. An excellent paint can sit for six months with no settling and rate a ten. Poor paint, however, will settle into an immiscible lump of pigment on the bottom of the can and rate a zero. Weathering is tested by exposing the paint to outdoor conditions. Artificial weathering exposes a painted surface to sun, water, extreme temperature, humidity, or sulfuric gases. Fire retardancy is checked by burning the paint and determining its weight loss. If the amount lost is more than 10 percent, the paint is not considered fire-resistant.

Byproducts/Waste

A recent regulation (California Rule 66) concerning the emission of volatile organic com-pounds (VOCs) affects the paint industry, especially manufacturers of industrial oil- based paints. It is estimated that all coatings, including stains and varnishes, are responsible for 1.8 percent of the 2.3 million metric tons of VOCs released per year. The new regulation permits each liter of paint to contain no more than 250 grams (8.75 ounces) of solvent. Paint manufacturers can replace the solvents with pigment, fillers, or other solids inherent to the basic paint formula. This method produces thicker paints that are harder to apply, and it is not yet known if such paints are long lasting. Other solutions include using paint powder coatings that use no solvents, applying paint in closed systerns from which VOCs can be retrieved, using water as a solvent, or using acrylics that dry under ultraviolet light or heat. A consumer with some unused paint on hand can return it to the point of purchase for proper treatment.

A large paint manufacturer will have an in house wastewater treatment facility that treats all liquids generated on-site, even storm water run-off. The facility is monitored 24 hours a day, and the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) does a periodic records and systems check of all paint facilities. The liquid portion of the waste is treated on-site to the standards of the local publicly owned wastewater treatment facility; it can be used to make low-quality paint. Latex sludge can be retrieved and used as fillers in other industrial products. Waste solvents can be recovered and used as fuels for other industries. A clean paint container can be reused or sent to the local landfill.

Where To Learn More

Books

Flick, Ernest W. Handbook of Paint Raw Materials, 2nd ed. Noyes Data Corp., 1989.

Martens, Charles R. Emulsion and Water- Soluble Paints and Coatings. Reinhold Publishing Company, 1964.

Morgans, W. M. Outlines of Paint Technology, 3rd ed. John Wiley & Sons, 1990.

The Paints and Coatings Industry. Business Trend Analysts, 1990.

Paints and Protective Coatings. Gordon Press, 1991.

Turner, G. P. A. Introduction to Paint Chemistry and Principles of Paint Technology, 3rd ed. Chapman & Hall, 1988.

Weismantel, Guy E. Paint Handbook. McGraw-Hill, 1981.

Periodicals

Levinson, Nancy. “Goodbye, Old Paint.” Architectural Record. January, 1992, pp. 42¬43.

Scott, Susan. “Painting with Pesticides: the Controversial Organoxin Paints.” Sea Frontiers. November/December, 1987, pp. 415-421.