Background

A saddle is a seat for the rider of an animal, usually a horse. A well-made saddle gives the horse rider the necessary support, security, and control over the animal. The saddle makes it possible for the rider to keep in balance with the horse by allowing him or her to sit over the horse’s point of balance.

The first saddles were simply animal skins or cloths thrown over the backs of horses, offering only a small measure of comfort to the riders. About 2,000 years ago, the Sarmatians, a nomadic tribe who lived around the Black Sea region, designed a saddle based on a shaped wooden foundation, or tree. The tree had front and rear arches joined by wooden bars on each side of the horse’s spine. This design, improved upon during the medieval era with the advent of the dip- seated saddle, survives in an adapted form as the Western saddle.

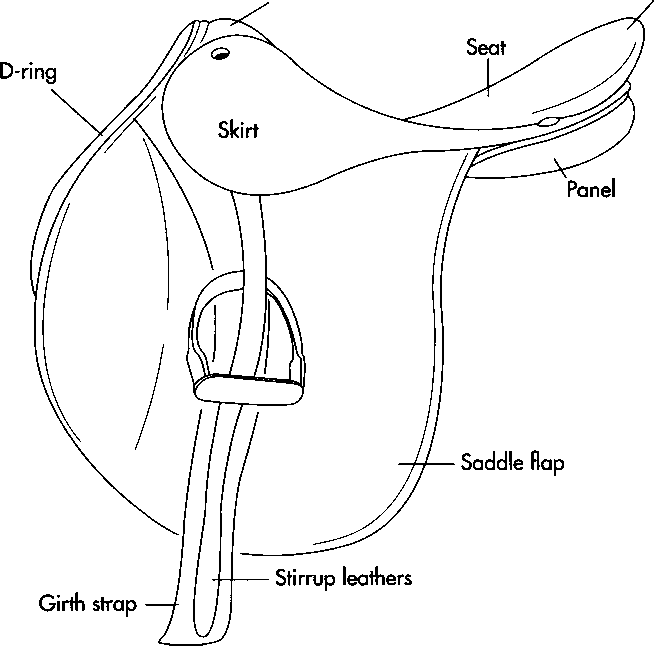

A typical saddle includes a base frame or “tree”; a seat for the rider; skirts, panels, and flaps that protect the horse from the rider’s legs and vice versa; a girth that fits around the stomach of the horse and keeps the saddle stable; and stirrups for the rider’s feet.

The saddle tree is the frame on which the saddle is built. Its shape determines the shape of the saddle, which varies from the flat-race tree weighing only a few ounces to the modem dip-seated spring tree. Ideally, the tree should be built to fit the back of the horse for which the saddle is intended. Most of the time, however, saddles are manufactured for certain sizes and shapes and will fit most horses of equivalent sizes and shapes. Trees are usually made in three width fittings: narrow, medium, and broad, and four lengths: 15 inches, 16 inches, 16 1/2 inches and 17 1/2 inches (38.1, 40.64, 41.9, and 44.45 centimeters respectively).

Panels are cushions divided by a channel that gives a comfortable padded surface to the horse’s back while raising the tree high enough to give easy clearance of the animal’s spine. The panels also disperse the rider’s weight over a larger surface, thereby protecting the horse from the weight of the rider. These panels also protect the horse’s back from the hardness of the saddle. The purpose of the skirts is to protect the rider’s legs from the sweat of the horse, and to cover the girths and girth straps. Saddles also include D- rings, small leather straps with strings attached that can hold canteens, jackets, food pouches, and other items.

Modem horse saddles are divided into two b’road categories: the English and Western saddle. Originally designed for show jumping, the English saddle has a deep seat and sloped back. Its design was derived in part from the crouched-forward position adopted by Tod Sloan, an American jockey, and the subsequent Italian design introduced by Caprilli in 1906. Sloan’s forward crouch placed the rider’s weight forward, thus freeing the horse’s loins and hindquarters. Because professional jockeys had previously positioned their weight on the loins and behind the movement of the horse, Sloan’s technique revolutionized professional horse racing.

One type of English saddle, the “jumping saddle,” is designed to position the rider more forward. It is almost always built on a spring tree and generally has a deep seat. In contrast, the “dressage saddle” is designed to position the rider more to the center of the horse, allowing him or her to use the leg and weight aids with greater precision. Only the sweat flap separates the rider’s leg from the horse. Today, English saddles are used for sport and general purposes.

Traditionally, the Western saddle has been used primarily for work. It has a wider and longer panel than the English saddle and disperses more of the rider’s weight over the back of the horse. Western saddles also have a roping horn on the pommel to facilitate the roping of cattle, and are equipped with extra D-rings, or tie-downs, to hold ropes and other items.

There are four types of Western saddles. The pleasure or “ranch saddle,” which weighs approximately 25 pounds (11.35 kilograms), and the “equitation saddle,” weighing about 25 to 30 pounds (11.35 to 13.62 kilograms), are suitable for general riding. The “roping saddle” (about 40 to 50 pounds [18 to 23 kilograms) is designed for use in cattle roping. Because of the comfort it provides, many find it suitable for general riding as well. The “cutting saddle” is slightly lighter, about 30 pounds, and is used in cow cutting competitions. Because its light weight allows for greater movement, some riders also find the cutting saddle suitable for general purposes.

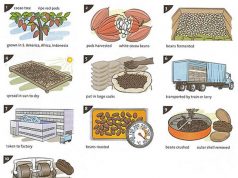

(The first step in saddle manufacture is treating the leather. This involves soaking the hide in a lime solution to loosen the outer layer of skin and the hair, and then removing the hair. The frame of the saddle is the tree. One typical tree type, the spring tree, is shaped out of thin plywood. Fiberglass material (the fiberglass looks like a white screen mesh) is then stretched over this plywood, and liquid resin is hand-brushed or sprayed on top, resulting in a very strong and durable product.)

Raw Materials

Flaps, girth straps, and stirrup leathers are typically made from animal skins taken from cattle, pig, sheep, or deer; cowhide is the Saddle trees can be composed of several materials, including beech wood, fiberglass, plastic, laminated wood, steel, aluminum, and iron. Seats are usually made from canvas, felt, and wool, while panels can include plastic foam, rubber, and linen.

The Manufacturing Process

Treating the leather

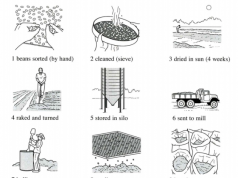

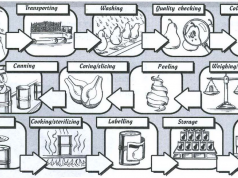

1 After the hide or skin is removed from the animal’s carcass, it is soaked in drums containing lime and other chemicals to loosen the hair and outer layer of the skin. The inside flesh layer is also removed, either by machine or hand with a special knife. The remaining hide is soaked in lime and bacteria solutions to remove residue. Next, the hair is removed, either by machine or manually with a special knife. The hide is soaked again, this time in an acid solution in order to remove the lime left by the previous soakings. Because it is important that the fleshy side is left smooth with no loose fibers, the hide undergoes a final treatment called scudding, which involves hanging the hide over a beam and removing any bits of remaining hair, tissue, and dirt with a blunt knife. The hide is then thoroughly washed.

2 To prevent hides from decaying, they are immersed in a diluted solution of tanning acid. Over several months, they are gradually treated with stronger solutions. Oil tanning, or chamoising, is still used sometimes by rubbing animal or fish grease into the hide.

3 At this point, the leather has two sides, the flesh side and the grain side. The hides are now given to a currier, who manually rubs a mixture of tallow, cod oil, and other greases, plus wax, into the leather over a period of time. This process gives the leather color, makes it flexible, durable, and waterproof. The most common and popular colors for saddles are golden yellow, also known as the London color, and Havana, which is of a darker shade. Warwick, a much darker color that turns black with use, is applied in the making of frizzing harness as opposed to riding tack. (This color is produced by staining with aniline dye.) The currier then allows the hides to mature for several weeks.

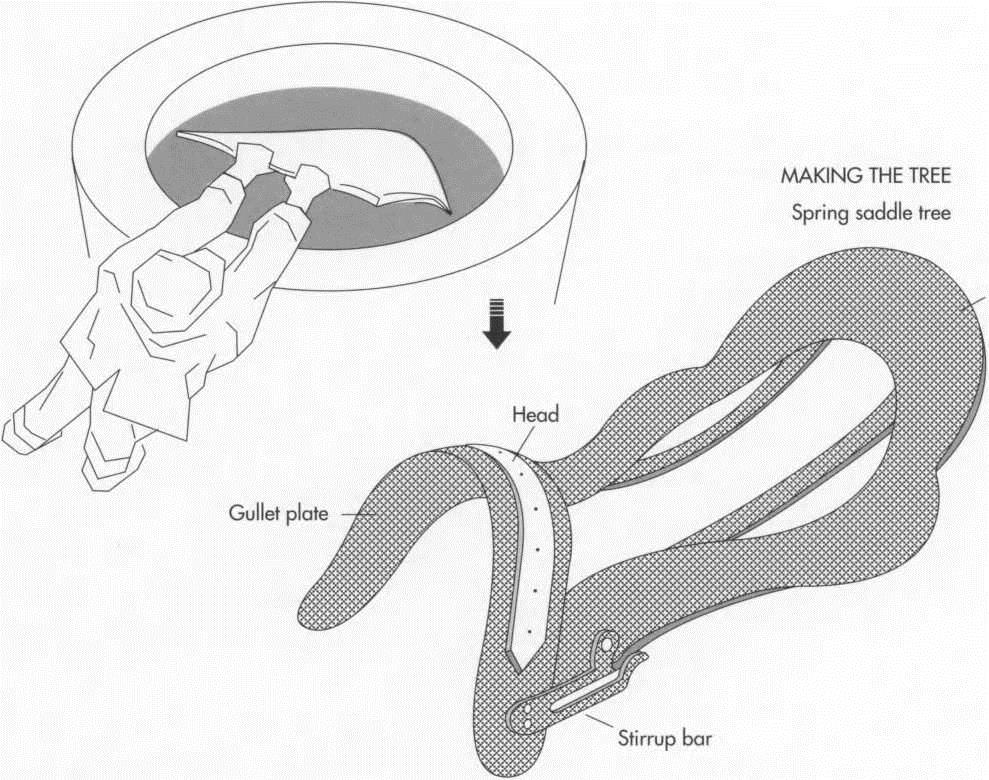

Making the saddle tree

4 There are two basic saddle tree designs: the rigid and spring tree, both of which can accommodate either a straight or dipped seat. The modem English saddle usually has a spring tree, while the Western saddle has a rigid tree.

The spring tree is first shaped out of thin plywood. Fiberglass material (the fiberglass looks like a white screen mesh) is then stretched over this plywood, and liquid resin is hand-brushed or sprayed on top, resulting in a very strong and durable product. Two “springs” made of lightweight steel strips are then inserted under the tree running from front to the rear along the widest part of the seat, and set about two inches (five centimeters) from the outside. The springs provide greater comfort and more flexibility to the rider by allowing the pressure exerted through the seat bones to be transmitted to the horse.

5 The rigid saddle tree is made by molding it out of fiberglass, by combining wood shavings with resin in a mold under pressure, or by creating a wooden tree around which wet leather strips are wrapped and allowed to dry.

6 To reinforce the saddle tree, steel plates are placed underneath the tree from the pommel (the head) to the cantle (the rear part of the saddle, which projects upward). The steel plates are secured above and below the pommel at the head and gullet of the tree.

Stirrups

7 The stirrup bars are attached next. A prong-line metal bracket measuring three inches wide is bolted onto the tree below the head on the point of the tree (the forward-most point of the saddle). Bars are made of two pieces: the bar itself, and a movable catch or “thumb piece,” which is set into the bar. This catch works on the premise that it can be opened when the stirrup leather is put in position and will, in theory, open and release the leather if the rider should fall. The bars are always forged (hammered or squeezed into the proper shape) or cast (put into a liquid state and forced into a shaped mold), and the word “forged” or “cast” is always stamped on the bar.

(A typical saddle includes a seat (or the rider; skirts, panels, and flaps that protect the horse from the rider’s legs and vice versa; a girth that fits around the stomach of the horse and keeps the saddle stable; and stirrups for the rider’s feet. D- rings are used to hold items such as canteens or ropes.)

8 The stirrup leathers, about 7/8 inch (2.2 centimeters) wide, are made from “read leather”: cowhide, rawhide, or buffalo hide. They go over the top of the bar and back down to the stirrups.

The seat

9 A strong muslin cloth is placed over the tree from the pommel to the cantle, to form a foundation. Pitch paint is then applied to waterproof it. Next, strips of white serge, a woolen material, are stretched and fastened tightly with small nails from the head of the tree at the pommel to the cantle. Stretch canvas is then positioned over the serge and nailed in place. This forms the base of the seat. Small pieces of shaped felt and leather (called bellies) are placed on the edges of the tree at the broadest part of the seat so that when the seat is eventually made, it will not drop away at the edges. A piece of serge is then tightly stretched and stitched down to the canvas layer to make the shape of the seat. Next, a small slit is made so that the space between the serge and canvas can be lightly stuffed with wool to give the seat resilience and to prevent the tree itself being felt through the leather seat.

1 1 Pigskin is now dampened and stretched I I tightly, and is then stretched over the seat. (The pigskin is dampened and stretched so that when it dries and shrinks, a neat and tight final product will be achieved.) The under panel, which protects the horse from the girths, is stitched and nailed into place on the tree. The under panel is usually made of pigskin leather or grained cowhide.

Girths

1 ^ Girth straps are attached to the saddle I ^ next. Made of soft leather, these straps are very short. Attached to them are the girths, whose purpose is to hold the saddle firmly in place by fastening them around the horse’s belly. These girths are made in 7/8- inch or one-inch (2.54 centimeters) thick sizes, and they can range in length from 36 inches (91.44 centimeters) for a tiny pony to 54 inches (137 centimeters) for a large horse (these measurements include the buckles). Girths are made of soft leather, mohair, or nylon.

Panels

1 Q The outer panels, made of leather, are I O stuffed with felt, wool, or plastic foam and are covered in either leather, serge, or linen. They are attached underneath the saddle. Leather skirts are then sewn just above the outer panel. D-rings (also known as tiedowns) are now attached to the saddle. Usually about one inch wide, the D-rings are made of rawhide and have strings attached to them.

Byproducts

Byproducts of saddle manufacturing include saddle and bridle accessories such as bit guards, lip straps, leather straps for the nose nets, breastplates, and girth safes, which prevent the buckles from wearing a hole in the panel.

Where To Learn More

Books

Baker, Jennifer. Saddlery and Horse Equipment: A Practical Horse Guide. Arco Publishing, 1982.

Beatie, Russel H. Saddles. University of Oklahoma Press, 1981.

The Complete Book of Riding: A Guide to Saddlery, Care and Management, International Breeds, Riding Techniques and Competitive Riding. Gallery Books, 1989.

Crabtree, Helen K. Saddle Equitation. Dou¬bleday, 1982.

Sherer, Richard L. Horseman ’s Handbook of Western Saddles. Sherer Custom Saddles, 1988.