Background

Shaving cream is a substance applied to the skin to facilitate removal of hair. Shaving cream softens and moistens the skin and the hair, thus making shaving more comfortable and contributing to smoother skin. The advantages of using shaving cream, rather than soap, oil, or just water, are many. Shaving with a modem bar of soap approximates shaving with cream but doesn’t provide all of the benefits: soap is only one element of many in a modem shaving preparation.

According to Burma Shave chronicler Frank Rowsome, Jr., modem shaving cream began with Burma Shave, which achieved high sales volume almost immediately after it was introduced. Prior to that time, lather was produced from a bar, and was basically another form of soap.

Manufacturing soap itself is an ancient craft—the word comes from the Old English word sape. By the seventh century, Italian soapmakers were organized in a guild, and, in the next century, the Holy Roman Emperor Charlemagne recognized soapmakers as craftsman. In the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries soap was made at Savona, Italy. The modem French, Spanish and German words for soap (savon, jabon, and seife, respectively) are cognates of the name of that town.

The early American settlers manufactured soap at home, using a method which called for mixing and heating animal fat with lye in a pot set over a fire, usually outdoors. This “open kettle” method of soap making was popular for years. Later adapted for large scale production, its use continued through the first half of the twentieth century.

By the eighteenth century, soap makers realized that they could enhance their product by improving the quality of the fat and the purity of the lye they used. Castile soap, made in Spain and still available today, soon achieved eminence as a face soap because of its smoothness and quality. Castile soap originally used olive oil rather than animal fat, and the modem version uses other fats and oils in addition to olive oil.

Although Americans continued to make their own soap at home for many years, they also began to manufacture soap commercially during the late seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries. Because they utilized similar materials and methods, soap makers were frequently in partnership with candle and tallow makers. The first soap maker to render (purify by melting) fats at his own operation was William Colgate, who had learned his trade in the early 1800s in New York City. The company that today bears his name is a tViajor producer of soap and other cosmetic preparations. In the nineteenth century storekeepers purchased soap from manufacturers in large blocks, from which their customers in turn cut smaller chunks. Jesse Oakley of Newburgh, New York, became the first manufacturer to sell wrapped soap in a cake form that was a good size for home use.

Soap was used for shaving through the early 1800s. In 1840, a concentrated soap that foamed was sold in tablets by Vroom and Fowler, whose Walnut Oil Military Shaving Soap was probably the first soap made especially for shaving. A century later, as the United States entered World War II, animal fats of relatively uncontrolled type and quality were still being used to make soap. To help supply American troops with soap, women were urged to save cans of cooking fat, and then bring them to local butchers who collected and delivered the fat to soap manufacturers. Because contaminants were inevitable in ingredients collected so haphazardly, the soap makers had to heat, strain, and reheat the fats—a process both inefficient and expensive. However, by the end of the war, mounting questions about purity and consistency led to the creation of the modem, regulated soap and cosmetic industry.

In addition to raising concerns about the quality of soap, World War II contributed to the invention of the spray can. Aerosol containers were first invented during the war as a device for dealing with insects carrying malaria and other diseases. Initially assigned to the Secretary of Agriculture, the patent for this “bug bomb” was released to American industry after the war. When the first aerosol shaving cream appeared in 1950, it captured almost one fifth of the market for shaving preparations within a short time. Today, aerosol preparations dominate the shaving cream market.

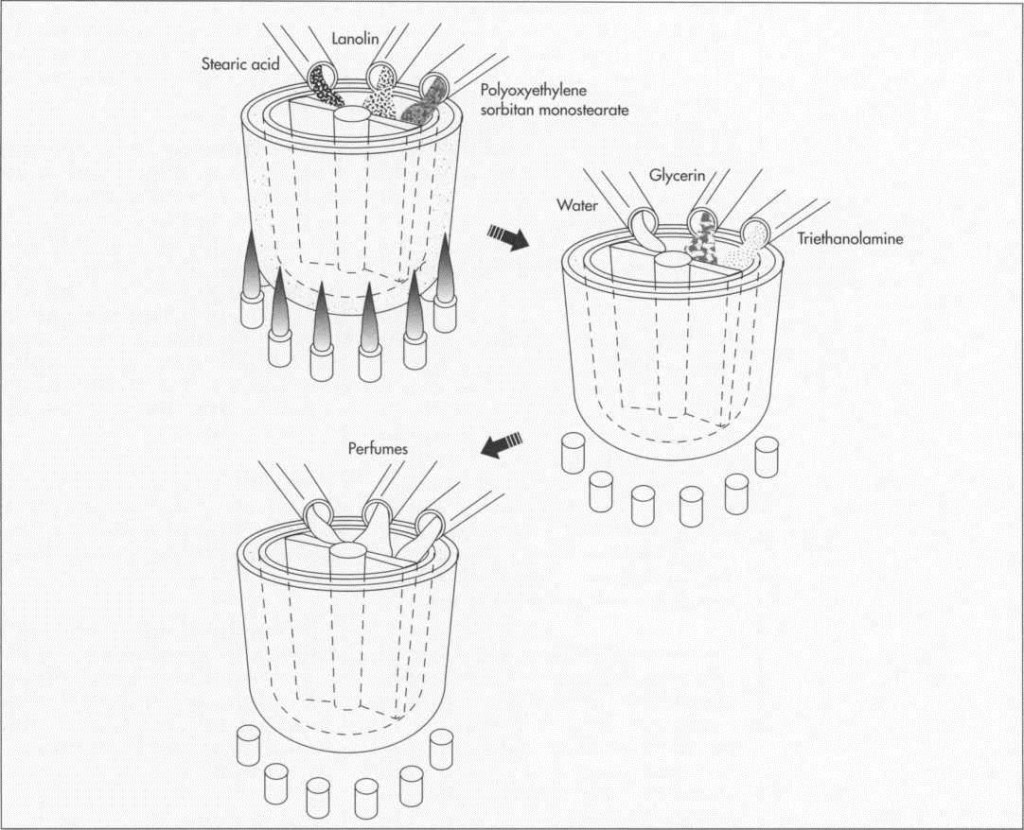

(In shaving cream manufacture, the fatty or oily materials are first combined and heated in a jacketed kettle, and then most of the remaining ingredients are added. The mixing continues while the mass cools, and then any desired perfumes are added.)

Raw Materials

The goal of any shaving preparation is to wet and soften the hair to be shaved, cushion the effect of the razor, and provide a residual film to soothe the skin. This film should be of the proper pH value: neither excessively alkaline nor overly acidic, it should correspond to the skin’s pH level.

Many manufacturers would have us believe that the recipes for shaving cream are carefully guarded secrets. However, the secrecy revolves mostly around the quantities in which standard ingredients are used, and the choice of substitutes for the few ingredients that are variable. By law, ingredients are listed right on the container, except for perfumes. Actual recipes are easily found in industrial chemistry textbooks available at many libraries. A standard recipe contains approximately 8.2 percent stearic acid, 3.7 percent triethanolamine, .5 percent lanolin, 2 percent glycerin, 6 percent polyoxyethylene sorbitan monostearate, and 79.6 percent water.

Two major ingredients in this formula are common in many of today’s preparations. Stearic acid is one of the main ingredients in soap making, and triethanolamine is a surfactant, or surface-acting agent, which does the job of soap, albeit much better. While one end of a surfactant molecule attracts dirt and grease, the other end attracts water. Lanolin and polyoxyethylene sorbitan monostearate are both emulsifiers which hold water to the skin, while glycerin, a solvent and an emollient, renders skin softer and more supple.

Common substitutes for the third, fourth, and fifth ingredients listed above include laureth 23 and lauryl sulfate (both sudsing and foaming agents), waxes, cocamides (which cleanse and aid foaming), and lanolin derivatives (emulsifiers). Most ingredients are powdered or flaked, although lanolin, lanolin derivatives, and cocamides are liquids.

The differences between one brand of shaving cream and another amount to adjustments in the proportions of ingredients and in the processing method (longer or shorter heating times, storage of the finished product, and so on), and choice of ingredients such as emulsifiers or perfumes. Also important is the choice of aerosol propellant. Some mixtures contain more than one propellant; most common are butane, isobutane, and propane. Though the wide range of choices for ingredients is well known, the exact combinations of ingredients represent the highest level of “magic” in modem chemistry.

The Manufacturing Process

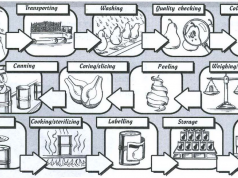

The modem manufacture of shaving cream is a carefully controlled process. Although carried out on a large scale, its manufacture resembles a laboratory procedure involving only small quantities of ingredients. There are two main phases to the manufacturing process.

1 ln the first phase, the fatty or oily portions of the formula—stearic acid, lanolin, and polyoxyethylene sorbitan monostearate—are heated in a jacketed kettle to a temperature of approximately 179 to 188 degrees Fahrenheit (80 to 85 degrees Celsius). The jacketed kettle, which can hold as little as 300 gallons or as much as 10,000 gallons, resembles a double boiler: one container, placed inside another, is heated when steam is circulated through the outer container. Inside the interior kettle are blades that revolve to mix the oils as they are heated.

2 After the first group of ingredients has turned smooth over a period of roughly 40 minutes, the steam is released from the outer container of the kettle, and the mixture is allowed to cool.

3 The second phase of manufacture begins when the mixture has cooled to about 152 degrees Fahrenheit (65 degrees Celsius). Most of the remaining ingredients—water, glycerin, and triethanolamine—are added now, and mixing continues for approximately 40 minutes.

4 When the mixture reaches a temperature of 125 to 134 degrees Fahrenheit (50 to 55 degrees Celsius), perfumes or other scents can be added. Because perfumes consist primarily of highly volatile oils, they would evaporate if added when the blend was still warm. The formulas for perfumes, which can contain more than 200 different ingredients, come closer to being trade secrets than information about shaving cream itself (though textbook and handbook formulas for perfume are not hard to come by). In recognition of this, manufacturers do not have to disclose information about fragrances.

5 The mixture, still being stirred, is allowed to cool further, until it reaches a temperature of 89 degrees Fahrenheit (30 degrees Celsius). Now a thickening white mass of highly viscous liquid, it is forced through a silk or stainless steel screen to eliminate any process, and to catch the rare impurity or foreign object such as a small wood splinter.

6 If this particular mixture is designated for tube packaging, it is now placed in a tube and fitted with a cap. After the bottom of the tube has been crimped, the product is ready for shipment and stocking on a store shelf.

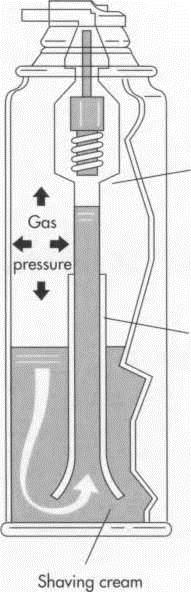

7 When the desired product is an aerosol spray, the shaving cream is poured into an open can. Next a valve and a cover are fitted onto the can and forced downward to form a seal. Propellant is then forced into the can through the valve. Most shaving preparations contain between four and five percent propellant; a larger amount would dry the shaving cream as it came out of the can, rendering it unusable. A small amount of material is intentionally released (purged) to relieve excess pressure, and the can is tested in water to make sure that the valve is holding tightly. The can is now ready to be shipped.

(In a typical aerosol can, the shaving cream ingredients occupy only a small portion of the can. The propellant or gas occupies 4 to 5 percent of the can; a larger amount would dry the shaving cream as it came out of the can, rendering it unusable)

Quality Control

Today’s soaps, shaving creams, and lotions are all manufactured under strict quality control, and regulated by various federal agencies including the Food and Drug Administration (FDA). Some states have their own regulatory agencies, though state agencies are more likely to focus on environmental concerns than product safety. Batches of shaving cream are examined and analyzed both at the manufacturing site and in the laboratory. Individual containers of shaving preparations are coded so that a manufacturer knows exactly which batch any given can or tube came from, and can identify its distribution history.

A manufacturer of shaving cream needs to be certain that each batch meets quality standards. Among the things tested for are pH value (the acidity or alkalinity of the product), the height of the foam when sprayed, and its absorption rate (spray the foam on a piece of paper—how long does it take till the bottom of the paper shows moisture?).

Water quality must also be checked carefully. Most manufacturers make sure the water they use is pure by exposing the water to ultraviolet light or using distilled water. Having a microbiologist on site to test the water and the final product is common in the industry. In a typical aerosol can, the shaving cream ingredients occupy only a small portion of the can. The propellant or gas occupies 4 to 5 percent of the can; a larger amount would dry the shaving cream as it came out of the can, rendering it unusable.

Where To Learn More

Books

DeNavarre, M. G. The Chemistry and Manu-facture of Cosmetics. Van Nostrand, 1962.

Lubowe, Irwin I. Cosmetics and the Skin. Reinhold Publishing Corp., 1964.

Men’s Shaving Products Market. Frost & Sullivan, 1990.

Winter, Ruth. A Consumer’s Dictionary of Cosmetic Ingredients, Crown, 1989.

Periodicals

Brooks, Geoffrey J. and Fred Burmeister. “Preshave and Aftershave Products.” Cosmetics and Toiletries. April, 1990, pp. 67-69.

“Creams and Lotions Formulary.” Cosmetics and Toiletries. November, 1986, pp. 139-70.

“Deodorants, Antiperspirants and Shaving Products Formulary.” Cosmetics and Toiletries. April, 1990, pp. 75-87.