Background

Neckwear dates back 30,000 years when primitive peoples adorned their chests with beads and bangles. Throughout the ages, people continued to wear wood, metal, pearls, feathers, glass, or cloth around their necks. Perhaps the superstition widely believed in the Middle Ages that bodily ills entered one through the throat had something to do with the continued popularity of a protective neckcloth, or perhaps soldiers felt more secure in having their neck covered in battle.

The first neckties, known as cravats, were worn by soldiers in the seventeenth century. According to legend, Croatian mercenaries, after having fought over Turkey, visited Louis XIV in Paris to celebrate their victory. The Sun King was so impressed by the colored silk scarfs the soldiers wore around their necks that he adopted the fashion himself. The mercenaries, called the Royal Cravattes (from the Croatian word kravate), lent their name to what became a popular fashion accessory. The style quickly spread to England after exiled Charles II returned from France, bringing with him his interest in cravats, and they have continued to be a part of men’s neckwear since then.

The stock tie, which appeared to be a well- tied knot in the front but was actually fastened at the back of the neck, was an alternative to the cravat for almost two hundred years, only to be forgotten by the early 1900s. The modern necktie became the norm in the twentieth century. Ninety-five million ties are sold in the United States annually, generating more than $1.4 billion in retail sales, according to MR Magazine and the Neckwear Association of America’s 1992 Handbook.

Raw Materials

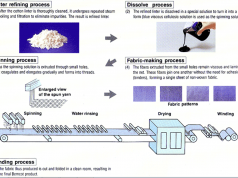

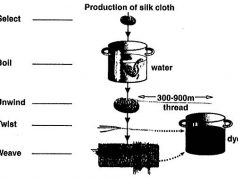

The most commonly used fibers for the manufacturing of neckties are silk, polyester, wool and wool blends, acetate, rayon, nylon, cotton, linen, and ramie. Neckties made from silk represent about 40 percent of the market. Raw silk is primarily imported from China and, to a far lesser extent, Brazil. Domestic weavers of tie fabrics buy their silk yam in its natural state and have it finished and dyed by specialists. Technological advances have made possible the use of microfiber polyesters, which produce a rich, soft fabric resembling silk and which can be combined with natural or other artificial fibers to produce a wide range of effects.

Design

The design of neckties is an interactive process between weavers and tie manufacturers. Because small quantities in any given pattern and color are produced, and because fabrics can be so complex, tie fabric weaving is seen as an art form by many in the industry.

Much of neckwear design is done in Como, Italy. If a new design is requested, time is spent developing ideas, producing sample goods, and booking orders against the samples. Most of the time, however, weavers work with open-stock items (designs that have been previously used and have a lasting appeal). Weavers use computerized silk screens, a process that has replaced the more time and labor-intensive manual silk-screening. When working with a standard design, the designer fills in each year’s popular colors, changing both background and foreground colors, making it broader or narrower, larger or smaller, according to demand. The manufacturer offers input and refinements in coloration and patterns. If willing to commit to a large amount of yardage, a manufacturer can also develop his or her own design and commission a weaver to produce it. Once the design is complete, it is sent to mills where it is imprinted onto 40-yard bolts of silk. The bolts of silk are then sent to the United States for manufacturing.

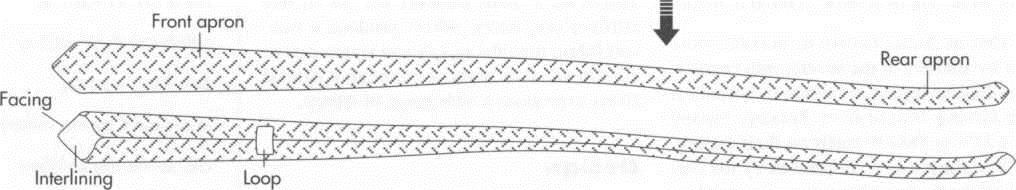

The main components of a necktie are the outer fabric, or shell, the interlining (both cut on the bias), and the facing or tipping, which is stitched together by a resilient slip-stitch so that the finished tie can “give” while being tied and recover from constant knotting. The quality of the materials and construction determines if a tie will drape properly and hold its shape without wrinkling.

A well-cut lining is the essence of a good necktie. This interlining determines not only the shape of the tie but also how well it will wear. Therefore, it must be properly coordinated in blend, nap, and weight to the shell fabric. Lightweight outer material may require heavier interlining, while heavier outer fabrics need lighter interlining to give the necessary hand, drape, and recovery. Most interlining manufacturers use a marking system to identify the weight and content of their cloths, usually colored stripes, with one stripe being the lightest and six stripes being the heaviest. This facilitates inventory control and manufacturing. A completed tie measures from 53 to 57 inches in length. Extra-long ties, recommended for tall men or men with large necks, are 60 to 62 inches long, and student ties are between 48 and 50 inches in length.

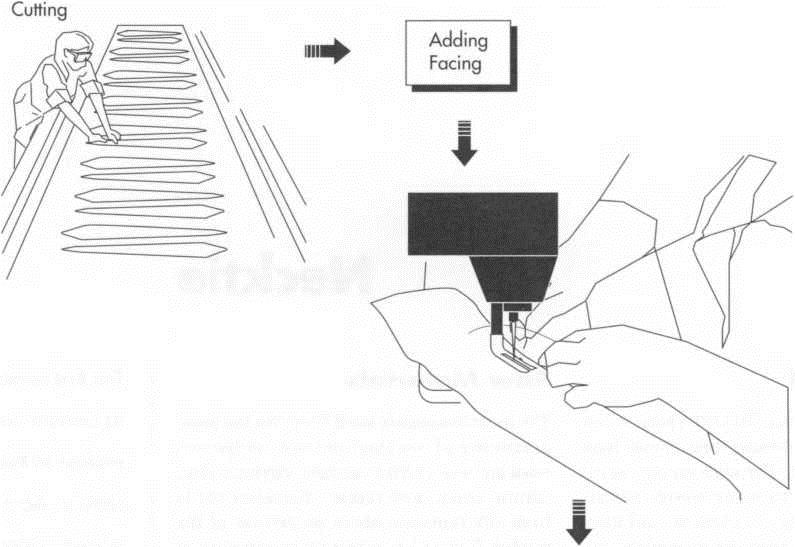

(The first step in the manufacture of neckties is cutting the pieces from 40-yard bolts of cloth. Next, using a sewing machine, workers join the tie’s 3 sections on the bias in the neckband area and then add the facing to the back of the tie’s ends. At this point, the tie is inside out. After the interlining is stitched to the tie, the tie is turned right-side out.)

The Manufacturing Process

Cutting the outer fabric

1 ln the workroom, an operator first spreads the 40-yard bolts of cloth on a long cutting table. Cutting the outer fabric is done by a skilled hand to maximize the yield, or the number of ties cut from the piece of goods. If the fabric has a random design, the operator stacks between 24 and 72 plies of fabric pieces in preparation for cutting the fabric. If pattern of the fabric (or of the “goods”) consists of panels, such as stripes with a medallion at the bottom, these panels are then stacked according to the pattern.

Adding the facing

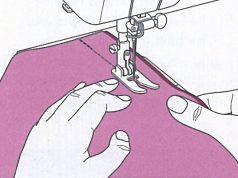

2 Using the chain stitch of a sewing ma-chine, sewing operators join the tie’s three sections on the bias in the neckband area. The operator now adds the facing, or tipping (an extra piece of silk, nylon, rayon, or polyester), to the back of the tie’s ends. Facing gives a crisp, luxurious hand to the shell. Two types of facing are currently utilized. Three-quarter facing extends six to eight inches upward from the point of the tie, while full facing extends even higher, ending just under the knot.

3 A quarter to a half of an inch of the shell of the fabric is now turned under, to form a point. The point is then machine-hemmed by the sewing operator.

Piece pressing

4 Quality silk ties are pocket or piece- pressed. This means that the joint at the neck (the piecing) is pressed flat so the wearer will not be inconvenienced by any bulkiness.

Interlining

5 The interlining is slip-stitched to the outer shell with resilient nylon thread, which runs through the middle of the tie. Most ties are slip-stitched with a Liba machine, a semi-automated machine that closely duplicates the look and resiliency of hand stitching. Hand stitching is often used in the manufacture of high-quality neckties because it offers maximum resiliency and draping qualities. The technique is characterized by the irregularly spaced stitches on the reverse of the tie when the seam is spread slightly apart; by the dangling, loose thread with a tiny knot at the end of the reverse of the front apron; and by the ease with which the tie can slide up and down this thread.

Turning the lining

6 Using a turning machine or a manual turner (with a rod about 9 1/2 inches long), an operator turns the tie right-side out by pulling one end of the tie through the other. While not yet pressed, the tie is almost complete. On silk ties only, the lining is then tucked by hand into the bottom comer of the long end of the tie. If necessary, the operator hand-trims the lining to fit the point of the long end. (In all other ties, the lining does not reach all the way to the bottom comer.)

7 A final piece to be sewn on is the loop, which serves both as a holder for the thin end of the tie when it’s being worn and as the manufacturer’s label.

The Future

Relatively recent disruptions in the supply of raw silk from China, in addition to technological advancements, have highlighted the advantages of using man-made fiber yarns. These artificial fibers are readily and dependably synthesized from domestic resources and are also usually yam-dyed. Microfiber polyester or nylon fibers (with a denier per filament count of one or less) can be bundled into yam finer than cotton and silk and can be combined with natural or other man-made fibers to produce a wide range of effects. Introduced into fabrics as air textured, false twist textured, or fully-drawn flat yams, they produce a rich, soft, silk-like hand.

Where To Learn More

Books

Boucher, Francois. 20,000 Years of Fashion: The History of Costume and Personal Adornment. Harry N. Abrams, Inc., Publishers, 1966.

Gibbings, Sarah. The Tie: Trends and Traditions. Barron’s, 1990.

History of Costume from Ancient Egypt to the Twentieth Century. Harper and Row Publishers, Inc., 1965.

Yarwood, Doreen. The Encyclopedia of World Costume. Charles Scribner’s and Sons, 1978.

Schoeffler, O. E. and William Gale. Esquire’s —Eva Sideman

Encyclopedia of 20th Century Men’s Fashions. McGraw Hill, Inc., 1973.