Background

Pantyhose are a form of sheer women’s hosiery that extend from the waist to the toes. The terms hosiery and stocking derive from the Anglo-Saxon words hosa, meaning “tight-legged trouser,” and stoka, meaning “stump.” When the upper part of a trouser leg was cut off, the remaining stoka became “stocking,” and hosa became “hosiery.” For centuries, sheer stockings and hose were worn as separate leg and foot coverings. However, after World War II, fashion designers began to attach panties to stockings, creating the form of hosiery currently favored by most women. Although their most basic purpose is to protect and beautify the feet and legs of female consumers, nylons are also put to other uses, including supporting the legs of football players and protecting crops from dust storms. Pantyhose have even been recycled in the arts and crafts industry, where they are cut up and stuffed with fiberfill to become the arms and legs of dolls and stuffed animals.

Few early references to women’s hosiery exist because any public mention of women’s legs was considered improper until the twentieth century. The first extant discussion of a garment resembling today’s pantyhose concerns the “tight-fitting hose” young Venetian men wore beneath short jackets during the fourteenth century. Made of silk, these leggings were often brightly colored and embroidered; older Venetians considered them extremely immodest. One of the earliest mentions of women wearing stockings appears in the records of Queen Elizabeth I, whose “silk woman” presented her with a pair of knitted black silk stockings. Admiring their softness and comfort, the Queen requested more, and wore only silk stockings for the rest of her life.

In 1589, when the Reverend William Lee at-tempted to patent the first knitting machine, Queen Elizabeth denied his request because, she contended, the coarse stockings produced by Lee’s machine were inferior to the silk hose she had shipped from Spain. Lee improved his machine, enabling it to manufacture softer stockings, but Elizabeth’s successor, James I, denied his second patent application as well, this time out of fear that the machine would endanger the livelihood of English hand knitters. After Lee’s death, his brother built a framework knitting machine that remained unrivalled for several hundred years.

When William Cotton invented the first automated knitting machine in 1864, he incorporated the key features of Lee’s design, notably the spring-beard needle that is still used in many contemporary knitting machines. Named for the fine, open hook that projects from the needle at an angle like that of the hair in a man’s beard, the spring-beard needle must be used with a pressing device to close the hook as it forms a loop. This type of needle is ideal for hosiery because it produces smaller loops and, consequently, a finer weave. Cotton’s straight-bar machine created flat sheets of fabric using a weft stitch whereby a continuous yam was fed to needles that sewed back-and-forth horizontal rows. By increasing or reducing the number of needles used to knit different portions of a stocking, workers could vary the thickness of the garment: more needles produced thicker fabric. Stitching began at the top of the stocking with a welt, or thick strip to which women could attach garters. To accommodate the feet and ankles, the stocking fabric was thinned at the bottom, although the fabric at the heel remained thick, for cushioning purposes. After it was removed from Cotton’s machine, the fabric was manually shaped and seamed up the back to produce so-called full-fashioned stockings.

Also produced during the mid-nineteenth century, the first seamless stockings were made on circular machines that knitted tubes of fabric to which separate foot and toe pieces were subsequently attached. Although these stockings were more attractive in that they featured no visible seams, they bagged at the knees and ankles because circular machines could not add or drop stitches like the Lee and Cotton machines. It was not until the World War Et era that two developments made possible better-fitting stockings. First, circular machines were improved so that they could Knit stockings in one piece. Still more significant was the DuPont Company’s invention of a synthetic fiber called nylon. After being sewn into a tube, nylon fabric could be heated and formed into a shape that it would thereafter retain through numerous stretchings and washings. Hosiery made from this revolutionary fabric was introduced to the general population in 1940, and its immediate popularity soon rendered the word “nylons” synonymous with hosiery.

However, the war that had accelerated the development of nylon also increased the demand for it, so, during the early forties, the hosiery industry offered socks instead of stockings. The anklet, a short cotton sock, became the temporary replacement favored by most women, particularly the young consumers known as “bobbysoxers.” Yet, when the war ended and nylon was once again available for consumer uses, most women returned to nylon stockings. During the sixties, decreasing skirt lengths necessitated longer stockings, and fashion designers created what we now know as pantyhose by attaching panties to hosiery. In addition to accommodating all hemline fluctuations, pantyhose don’t need to be held up with the garters and garter belts previously used to secure stockings. Nylons have become a fashion accessory that few women are willing to do without. This is especially true in the white- collar workforce, where they are considered an essential part of appropriate office attire.

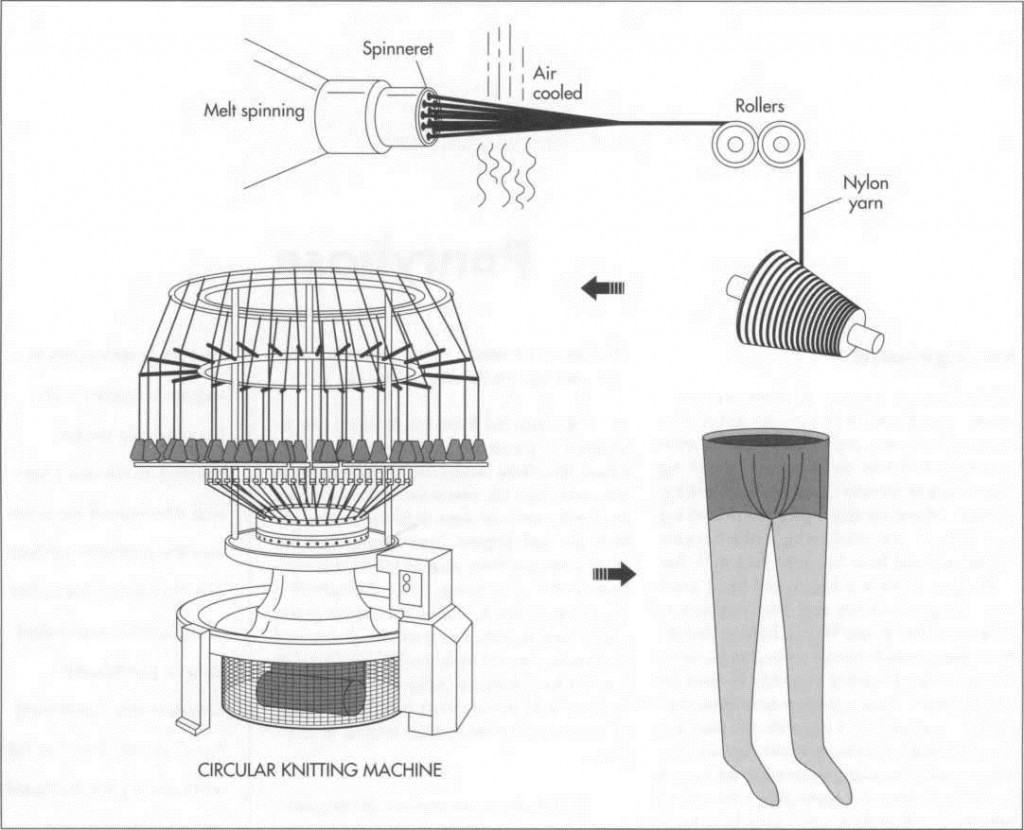

(Nylon is made in a process known as “melt spinning.” First, a syrupy polymer solution is produced and then extruded through a spinneret. As the nylon strings emerge, they are cooled by air and stretched over rollers to stabilize the molecular chains and strengthen the fibers. The yarn is then wound on spools. Next, the yarn is fed into a computer-controlled circular knitting machine, which uses its 300 to 420 needles to convert the nylon into a series of loops. It takes about 90 seconds to knit a full-length slocking leg )

Raw Materials

Pantyhose are generally made from a nylon- based blend of synthetic fibers. The nylon most commonly used—Nylon 6,6—is made from adipic acid, an organic acid, and hexa-methylene diamine, an organic base, which are chemically combined to form a nylon salt. Because nylon is a plastic material—actually the first thermoplastic fiber ever used—the salt must undergo polymerization. In this process, different molecules are combined to form longer molecular chains. These chains result in a smooth, thick substance that is then cut into small shapes or pellets, before being spun into yarn. The nylon fiber’s size, strength, weight, elasticity, and luster are determined during its preparation by controlling the number and type of filaments used. For example, luster is produced by adding titanium dioxide (TiOi). The resulting fiber is highly elastic and retains its shape after repeated washings and stretchings. Its resistance to wrinkles and creases, its durability, and the fact that it dries quickly make it a desirable fabric for busy women.

Today, filaments of another synthetic fiber, spandex, are frequently combined with nylon filaments to increase elasticity and achieve a snugger fit. More recently, other new fibers known as microfibers or microdeniers have been blended with nylon. A denier is a unit of measure that indicates the thickness of nylon yam. The denier scale ranges from 7 to 80 denier, with smaller numbers indicating finer yarn and higher numbers denoting heavier yarn that will be used to make stronger fabrics. When blended with nylon, microdeniers enhance softness, hold color more evenly, and provide a better fit.

Design

Pantyhose are usually classified as sheer, semisheer, or service weight, with the weight determined by the denier and the number of needles used during production. Although stockings do not differ in shape, fashion designers will vary the color, texture and pattern of their hosiery. Much as the fashion industry offers different types of clothing appropriate for specific functions and occasions, it designs hosiery tailored to particular purposes. For example, heavier knit and natural colored pantyhose are considered more practical for daytime and office wear while sheer hosiery is saved for evening affairs and special occasions. Similarly, darker nylons are generally found on retail shelves during the winter, while paler shades are displayed in the spring and summer. In addition, some designers offer hose with extra elastic sewn in to the midriff to serve as “tummy control”; still others produce nylons with lightweight girdles instead of panties. Because nylon does not “breathe” well, some manufacturers offer hosiery with cotton crotch panels, and both toes and heels can be reinforced to deter runs.

The Manufacturing Process

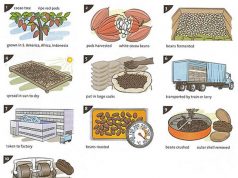

Making nylon yarn

1 Nylon yam is made in a process known as melt spinning. First, the chemicals involved—adipic acid and hexamethylene damine—must be polymerized to form a thick resin that is then cut into chips or pellets. These pellets are then heated and pressurized in an autoclave into a syrupy solution. Next, the solution is extruded through a spinneret—a device that looks and works like a shower head, with long strings of nylon solution coming out of the holes in the device. The number of holes depends on the type of yam desired: one hole produces monofilament yam, which is very thin and sheer; several holes produce multifilament yam, which is denser and less sheer. As the fibers emerge from the spinneret, they are cooled by air and then stretched over rollers to stabilize the molecular chains and strengthen the fibers. The yam is then wound on spools.

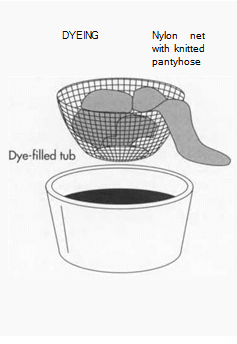

(After ifie legs are seamed together and the toe openings closed, the pantyhose garments are immersed in a dyeing machine. A modem dye machine can color about 3,500 dozen pairs of hose a day. After drying and boarding—steaming the hose to the proper shape—the garments are ready for packaging)

Knitting

2 Yam is fed into a circular knitting machine, which converts it into a series of loops. Usually computer-controlled, the machine contains 300 to 420 needles and rotates at speeds up to 1,200 RPM; it takes about 90 seconds to knit a full-length stocking leg.

Seaming

3 Next, openings at the toes are seamed together, and two stocking legs are seamed together to form pantyhose. Sometimes they are seamed together with a crotch. Like the other steps in pantyhose manufacture, seaming is almost completely automated.

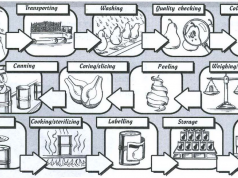

Dyeing and drying

4 The sewn product then goes to a dye ma-chine where it will be dyed to one of more than 100 different shades. The dye machine can color about 3,500 dozen pairs a day. Once dyed, the pantyhose are taken to a compartment dryer which dries them.

Boarding

5 This next step, boarding, is sometimes done before the dyeing process, depending on the desired final product. Boarding is the process of placing the pantyhose over leg forms where they are steamed and heated to the desired shape. With less expensive hosiery, this step may be completely bypassed and the pantyhose packaged in their relaxed state.

Inspecting

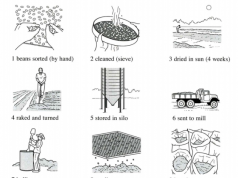

6 Throughout the manufacturing process, quality checks are performed on the pantyhose. A statistical method is used for inspection.

Packaging

7 Pantyhose that meet the inspection guide-lines are packaged in a box or paperboard envelope, either manually or automatically.

Filling orders: Picking and shipping

8 After they leave the manufacturing plant, the pantyhose are stored in warehouses and organized according to size, style, and color for efficient order-filling. Customer orders are filled by personnel at various “picking” stations positioned alongside a conveyor belt that carries the filled cases to a staging area for final shipping to retail markets.

Byproducts/Waste

The hosiery industry must confront the problems all textile mills face in producing a fabric. In particular, hosiery mills must treat the wastewater generated during the dyeing phase to prevent contamination. Many of the dyes used to tint pantyhose contain toxic substances such as ammonium sulfate. To minimize harmful wastewater, manufacturers must adhere to guidelines set by the U.S. government’s Environmental Protection Agency (EPA). Treating the water before it is dumped into rivers has alleviated some of the wastewater concerns. Another approach has been to control the amounts of various chemicals used during the manufacturing process. Failure to measure chemicals properly can create an over-abundance of some of the materials, thereby causing harmful waste. A third idea has been to substitute less harmful chemicals when possible.

The Future

The hosiery industry currently produces almost 2 billion pairs of women’s sheer hose annually. Industry analysts predict that consumers will continue to demand high-quality nylons in a variety of shades, styles, and degrees of sheemess. Manufacturers will strive to meet the consumer’s need by experimenting with hybrid fabrics that combine synthetic fibers with natural fibers such as cotton.

Where To Learn More

Books

Corbman, Bernard P. Textiles: Fiber to Fabric, 6th ed. McGraw-Hill, 1983.

Farrell, Jeremy. Socks and Stockings. Drama Book Publishers, 1992.

Grass, Milton N. History of Hosiery. Fairchild Publications, 1955.

Wingate, Isabel B. and June F. Mohler. Textile Fabrics and Their Selection, 8th ed. Prentice-Hall, Inc. 1984.

Pamphlets

National Association of Hosiery Manufacturers. Hosiery, The Opportunity Industry.