Background

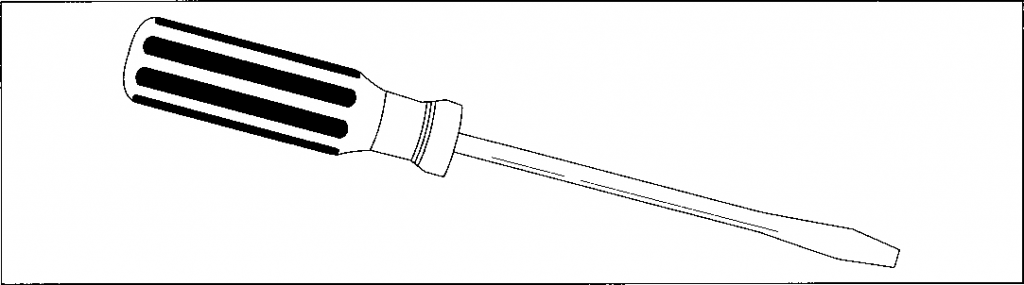

It would be very difficult to find an American household that did not have at least one screwdriver. Perhaps the most ubiquitous of hand tools, the screwdriver has a long genealogy, the result of a complicated manufacturing process. Archimedes is considered to have invented the screw in the third century B.C., though his invention was designed to transfer motion (as in the continuous worm of a worm and gear assembly) rather than to fasten things together.

By the first century B.C., large wooden screws were used in presses for producing wine and olive oil, and were turned with spikes stuck into or through a handle that resembled a modern corkscrew used for opening wine bottles, although larger. These were made of wood with a flat rather than a pointed end, and a container to hold the material being pressed.

Metal screws and nuts seem to have been used as fasteners in the fifteenth century, although the heads of these screws were turned with a wrench and not a screwdriver— the screw heads were either square or hexagonal. Screws with slots in their heads were found in armor in the following century, although the design of the tool used to work the screws, the screwdriver, is unknown.

The modern screwdriver descends directly from a flat-bladed bit used in a carpenter’s brace circa 1750. Woodworkers were using hand screwdrivers in the early 1800s, and they became more common after 1850, when machines made the automatic production of screws possible. These early screwdrivers were flat throughout the length of their shaft; the current design of a rounded bar that is flattened or shaped only at the working end makes the tool much stronger and takes advantage of the round wire used in its manufacture. The oldest and most common type of screwdriver is the slotted screwdriver, which fits a screw with a single slot in the head. There are perhaps thirty different types of screwdrivers available today in a variety of sizes, all with different purposes and all designed to fit into special screws.

The second most widely used screwdriver, the “Phillips,” was invented in the late 1920s by Henry Phillips. Soon after its introduction, the tool posed a dilemma for its user— the head of the driver pulls away from the screw as it is fastened, or “cam-out,” leading to stripped screw heads and assemblies that are difficult to take apart. However, cam-out became a virtue; the screws were meant to be driven with a power tool, and the assembler would know that the screw was completely driven when his power tool slid out of the screw head. A screw head that could accept the greater torque (turning power) of a power tool was an advantage over hand-turned, slotted screw heads. Today, manufacturers are producing or gearing up production of Phillips screwdrivers that eliminate cam-out. Possible solutions (although details of some systems are company secrets) focus on the angle of the edges that fit into the Phillips screw, or using a better gripping material to coat or plate the screwdriver tip.

The torx screwdriver, widely used for auto-mobile repair and other applications, was designed to take the torque that a Phillips screw can while eliminating the cam-out problem. It has six edges in a star pattern on its flat point, and fits flat into the screw head. It is not unusual to find torx drivers sold in a set with slotted and Phillips screwdrivers.

Other types of screwdrivers have been designed for special uses, and a well-stocked hardware store will have slotted, Phillips, torx, Robertson (a square shaft that fits into a corresponding square cut out in the head of the screw), and other more obscure types of screwdrivers. Some screwdrivers have not found a ready market, such as one that was designed to fit into special screws that have slots both on the top of the screw and on the side of the screw head, with corresponding grippers on the point of the screwdriver. There are so many screwdrivers and types of screws available that even a high quality of design innovation is overcome by consumer resistance to purchasing new types of screwdrivers and corresponding screws.

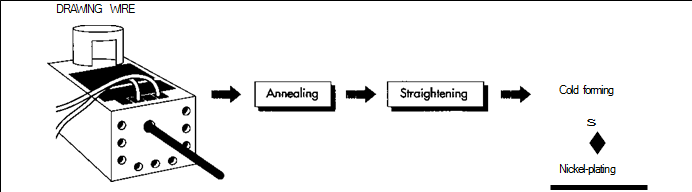

(To make the steel rod, wire is machine-drawn to the appropriate diameter, annealed (heat-treated), straightened, and then cold-formed to the proper shape. The cold forming press cuts the wire to the desired length and forms the tip of the screwdriver and the “wings” that will fit into the handle. The rod is then nickel-plated to give it a protective finish.)

Raw Materials

The raw materials for most screwdrivers are very basic: steel wire for the bar and plastic (usually cellulose acetate) for the handle. In addition, the steel tips are generally plated with nickel or chromium.

The Manufacturing Process

Making a flat-tip or slotted screwdriver is not very different than making any other configuration. Variations between a flat-tip and a Phillips screwdriver will be discussed later in this entry.

Making the steel bar

1 First, coils of green wire (wire that has not yet been drawn to final size) are delivered to a factory in large coils, some as heavy as 3,0 pounds (1,362 kilograms). The wire is usually about .375 inch (.95 centimeter) in diameter. The wire is then machine-drawn to the diameter necessary for the production run; one adjustable drawing machine can produce any required diameter. In drawing, wire is fed through a die with a reducing aperture until it assumes the proper size.

2 After the wire is drawn, it is annealed (heat treated) to obtain the correct tensile strength in the metal. This process involves baking the wire at a temperature of about 1,350 degrees Fahrenheit (732 degrees Celsius) for 12 hours.

3 Next, the wire is straightened by a string forge and then transferred to a cold forming press, which cuts the wire to the appropriate length and forms the tip of the screwdriver and the “wings” that will fit into the handle. These wings can be seen through a clear or semi-clear plastic handle. The newly formed “bar” (the actual screwdriver without its handle) is then heat treated in an in-line furnace at approximately 1,555 degrees Fahrenheit (846 degrees Celsius). This is a continuous flow process, and as the bars come through the furnace they fall into an oil quench for cooling. The bars are then placed in a drawback oven (450 to 500 degrees Fahrenheit or 232 to 259 degrees Celsius) and baked to a specified hardness.

4 Consumer model screwdrivers are nickel plated—covered with a protective coating of nickel—before assembly. If the screwdriver is designated for professional use, it is transferred to a hand-grinding department, where the tip is ground to size. The shank is chemically milled and then polished. The screwdriver then goes to a nickel flash bath

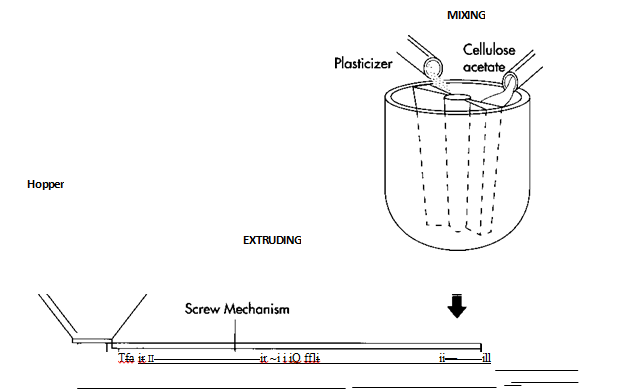

(The plastic handles are made by mixing cellulose acetate with a plasticizer and then extruding the mixture into bar form. After further shaping, the bars are drilled so that the rods can be inserted, cleaned to remove dirt, and dipped in an acetone vapor bath, which melts and smooths the outside of the handle.)

Phillips screwdrivers

5 After the cold forming press (step #3 above) cuts the wire, the screwdriver is sent to a “swage and grind” operation, where dies form blades for the tip from the heated wire. The tool is then ground and the wings are formed.

6 If a professional model is being produced, the bar goes to a tipping operation (an automatic tipping machine that creates the bullet point), and then to a profilator machine (a machine that cuts a “profile”). This latter machine cuts the four grooves or slots on the sides above the point. The wire is then winged, and heat-treated in the same way as the flat-tip screwdriver bars. Consumer model Phillips screwdrivers are nickel plated, while the professional model is polished and nickel/chrome plated.

Handles

7 The handles of a screwdriver are usually made of cellulose acetate; it is delivered to the factory in powder form (cellulose acetate rosin) and then mixed with a liquid plasticizer in a giant blender that holds approximately 1,000 pounds (454 kilograms) of the mixed material. If a colored handle is desired, pigments are added into the blender. The resulting paste, which has the consistency of thick cake batter, then goes to an extruder (a machine that forces a material out through an opening, the way a meat grinder forces out strings of meat), which extrudes a solid piece of cellulose acetate. The cellulose acetate is then cut into small pellets.

8 Next, the pellets are fed into another extruder that extrudes the materials for the handles in bars that are 8 to 10 feet (2.4 to 1 meters) in length. If a two-color handle is desired, a second extruding machine can be attached to the first to extrude a single, two- color rod. The rods are then put into an automatic turning machine, which shapes the handles and cuts them to the final length. A hole is then drilled in the handle where the bar will be inserted.

(The oldest and most common type of screwdriver is the slotted screw-driver, which fits a screw with a single slot in the head. There are perhaps thirty different types of screwdrivers available today in a variety of sizes, all with different purposes and all designed to fit into special screws.)

The handles are machine washed and dried to remove grease, oil, and excess scraps from the turning machine and the extruder. Next, the handles are immersed in an acetone vapor bath, which melts and smooths the outside of the handle. The acetone vapor is highly flammable, and this process takes place inside an explosion-proof room.

Assembly

The method of final assembly depends on the quality of the tool being produced. Professional models are assembled individually on a horizontal assembly machine that hydraulically forces the bar into the plastic handle. The handles are branded by a hot stamp immediately before going into the assembly machine. This assembly process requires one skilled operator for each machine.

Other models might be assembled on hydraulic presses, three at a time. The least expensive models are assembled six at a time on one machine and placed by robot on a skin card machine that packages the screwdrivers for mass-market sale.

Before packaging, the screwdrivers might be fitted with a special handle cover, depending on need. A rubber cap fitted over a screwdriver handle, for example, might be more comfortable for a professional using his tool five or six hours a day. A large handle with deep grooves might be ideal for some workers, while the home handyman who assembles a lamp or cabinet once every six months may not need or want to pay for the extra comfort.

Quality Control

Consumer Reports magazine found, in 1983 tests, that the type of finish had little effect on the quality of screwdrivers, although most of their tested screwdrivers were plated. Poor-quality plating, on the other hand, might indicate that not enough care was paid to the tool in the manufacturing process. Similarly, poor-quality grinding can lead to rounded edges and comers which will not be as efficient as they could be; a tip that was burned during the grinding process may not be as hard as it should be.

Where To Learn More

Books

Hoffman, E. Fundamentals of Tool Design. T/C Publications, 1984.

Pollack, Herman W. Tool Design. Prentice Hall, 1988.

Self, Charles R. Fasten It. TAB Books, 1984.

Watson, Aldren A. Hand Tools: Their Ways and Workings. Portland House, 1982.

Periodicals

Bailey, Jeff. “Does Henry Phillips, Bane of Handymen, Really Rest in Peace?” Wall Street Journal, September 15, 1988, p. 4.

“Screwdrivers,” Consumer Reports. January, 1983, pp. 44-7.

Kinghorn, Bob. “The New Age of Screw- driving,” Family Handyman. October, 1989, p. 12.

Yeaple, Frank. “Zinc’s Properties Enhance Hand Tool’s Producibility,” Design News. January 22, 1990, p. 115.

Pierson, John. “Screwdriver Redesign Aims to Lock Out Slips,” Wall Street Journal. Jan¬uary 22, 1991, pp. 1-2.