Background

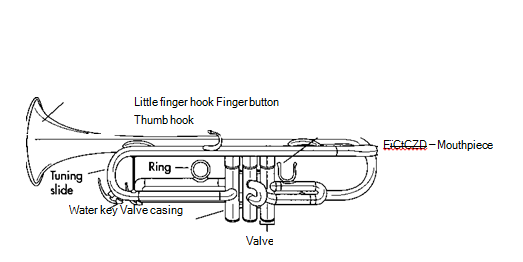

A trumpet is a brass wind instrument noted for its powerful tone sounded by lip vibration against its cup-shaped mouthpiece. A trumpet consists of a cylindrical tube, shaped in a primary oblong loop that flares into a bell. Modern trumpets also have three piston valves as well as small, secondary tubing that act as tuning slides to adjust the tone. Almost all trumpets played today are B-flat. This is the tone naturally played when the trumpet is blown. They have a range between the F- sharp below middle C to two and a half octaves above (ending at B), and are comparatively easier to play than other brass instruments.

The first trumpets were probably sticks that had been hollowed out by insects. Numerous early cultures, such as those in Africa and Australia, developed hollow, straight tubes for use as megaphones in religious rites. These early “trumpets” were made from the horns or tusks of animals, or cane. By 1400 B.C. the Egyptians had developed trumpets made from bronze and silver, with a wide bell. People in India, China, and Tibet also created trumpets, which were usually long and telescoped. Some, like Alpine horns, rested their bells on the ground. Assyrians, Israelites, Greeks, Etruscans, Romans, Celts, and Teutonic tribes all had some form of horn, and many were decorated. These instruments, which produced low, powerful notes, were mainly used in battle or during ceremonies. They were not usually considered to be musical instruments. To make these trumpets, the lost-wax method was used. In this process, wax was placed in a cavity that was in the shape of a trumpet. This mold was then heated so that the wax melted away, and in its place molten bronze was poured, producing a thick-walled instrument.

The Crusades of the late Middle Ages (A.D. 1095-1270) caused most of Europe to come into contact with Arabic cultures, and it is believed that these introduced trumpas made from hammered sheets of metal. To make the tube of the trumpet, a sheet of metal was wrapped around a pole and soldered. To make the bell, a curved piece of metal shaped somewhat like an arc of a phonograph record was dovetailed. One side was cut to form teeth. These teeth were then splayed alternately, and the other side of the piece of metal was brought around and stuck between the teeth. Hammering the seam smoothed it down. Around A.D. 1400 the long, straight trumpets were bent, thus providing the same sound in a smaller, more convenient instrument. Molten lead was poured into the tube and allowed to solidify. This was then beaten to form a nearly perfect curve. The tube was next heated and the lead was poured out. The first bent trumpets were S-shaped, but rapidly the shape evolved to become a more convenient oblong loop.

A variety of trumpets were developed during the last half of the eighteenth century, as both musicians and trumpet makers searched for ways to make the trumpet more versatile. One limitation of the contemporary trumpet was that it could not be played chromatically; that is, it could not play the half-step range called the chromatic scale. In 1750 Anton Joseph Hampel of Dresden suggested placing the hand in the bell to solve the problem, and Michael Woggel and Johann Andreas Stein around 1777 bent the trumpet to make it easier for the player’s hand to reach the bell. The consensus was that this created more problems than it solved. The keyed trumpet followed, but it never caught on, and was replaced rapidly by valve trumpets. The English created a slide trumpet, yet many thought the effort to control the slide wasn’t worth it.

The first attempt to invent a valve mechanism was tried by Charles Clagget, who took out a patent in 1788. The first practical one, however, was the box tubular valve invented by Heinrich Stoelzel and Friedrich Bluhmel in 1818. Joseph Riedlin in 1832 invented the rotary valve, a form now only popular in Eastern Europe. It was Francois Perinet in 1839 who improved upon the tubular valve to invent the piston valved trumpet, the most preferred trumpet of today. The valves ensured a trumpet that was fully chromatic because they effectively changed the tube length. An open valve lets the air go through the tube fully. A closed valve diverts the air through its short, subsidiary tubing before returning it to the main tube, lengthening its path. A combination of three valves provides all the variation a chromatic trumpet needs.

The first trumpet factory was founded in 1842 by Adolphe Sax in Paris, and it was quickly followed by large-scale manufacturers in England and the United States. Standardized parts, developed by Gustave Auguste Besson, became available in 1856. In 1875 C. G. Conn founded a factory in Elkhart, Indiana, and to this day most brass instruments from the United States are manufactured in this city.

Today some orchestras are not satisfied with only using B-flat trumpets. There has been a revival of natural trumpets, rotary trumpets, and trumpets that sound higher than the standard B-flat. Overall, however, modem trumpets produce high, brilliant, chromatic musical tones in contrast with the low, powerful, inaccurate trumpets of the past.

Raw Materials

Brass instruments are almost universally made from brass, but a solid gold or silver trumpet might be created for special occasions. The most common type of brass used is yellow brass, which is 70 percent copper and 30 percent zinc. Other types include gold brass (80 percent copper and 20 percent zinc), and silver brass (made from copper, zinc, and nickel). The relatively small amount of zinc present in the alloy is necessary to make brass that is workable when cold. Some small manufacturers will use such special brasses as Ambronze (85 percent copper, 2 percent tin, and 13 percent zinc) for making certain parts of the trumpet (such as the bell) because such alloys pro-duce a sonorous, ringing sound when struck. Some manufacturers will silver- or goldplate the basic brass instrument.

Very little of the trumpet is not made of brass. Any screws are usually steel; the water key is usually lined with cork; the rubbing surfaces in the valves and slides might be electroplated with chromium or a stainless nickel alloy such as monel; the valves may be lined with felt; and the valve keys may be decorated with mother-of-pearl.

Design

Most trumpets are intended for beginning students and are mass produced to provide fairly high quality instruments for a reasonable price. The procedure commonly used is to produce replicas of excellent trumpets that are as exact as possible. Professional trumpeters, on the other hand, demand a higher priced, superior instrument, while trumpets for special events are almost universally decorated, engraved with ornate designs. To meet the demand for custom-made trumpets, the manufacturer first asks the musician such questions as: What style of music will be played? What type of orchestra or ensemble will the trumpet be played in? How loud or rich should the trumpet be? The manufacturer can then provide a unique bell, specific shapes of the tuning slides, or different alloys or plating. Once the trumpet is created, the musician plays it and requests any minor adjustments that might need to be made. The trumpet’s main pipe can then be tapered slightly. The professional trumpet player will usually have a favorite mouthpiece that the ordered trumpet must be designed to accommodate.

The Manufacturing Process

The main tube

1 The main tube of the trumpet is manufactured from standard machinable brass that is first put on a pole-shaped, tapered mandrel and lubricated. A die that looks like a doughnut is then drawn down its entire length, thus tapering and shaping it properly. Next, the shaped tube is annealed—heated (to around 1,0 degrees Fahrenheit or 538 degrees Celsius) to make it workable. This causes an oxide to form on the surface of the brass. To remove the oxidized residue, the tube must be bathed in diluted sulfuric acid before being bent.

2 The main tube may be bent using one of three different methods. Some large manufacturers use hydraulic systems to push high pressure water (at approximately 27,580 kilopascals) through slightly bent tubing that has been placed in a die. The water presses the sides of the tubing to fit the mold exactly. Other large manufacturers send ball bearings of exact size through the tubing. Smaller manufacturers pour pitch into the tube, let it cool, then use a lever to bend the tube in a standard curve before hammering it into shape.

(Trumpets are almost universally made From brass, but a solid gold or silver trumpet might be created for special occasions. The most common type of brass used is yellow brass, which is 70 percent copper and 30 percent zinc. Other types include gold brass (80 percent copper and 20 percent zinc), and silver brass (made from copper, zinc, and nickel). The relatively small amount of zinc present in the alloy is necessary to make brass that is workable when cold)

The bell

3 The bell is cut from sheet brass using an exact pattern. The flat dress-shaped sheet is then hammered around a pole. Where the tube is cylindrical, the ends are brought together into a butt joint. Where the tube begins to flare, the ends are overlapped to form a lap joint. The entire joint is then brazed with a propane oxygen flame at 1,500 to 1,600 degrees Fahrenheit (816 to 871 degrees Celsius) to seal it. To make a rough bell shape, one end is hammered around the horn of a blacksmith anvil. The entire tube is then drawn on a mandrel exactly like the main tube, while the bell is spun on the mandrel. A thin wire is placed around the bell’s rim, and metal is crimped around it to give the edge its crisp appearance. The bell is then soldered to the main tube.

The valves

4 The knuckles and accessory tubing are first drawn on a mandrel as were the tube and bell. The knuckles are bent into 30-, 45-,60-, and 90-degree angles, and the smaller tubes are bent (using either the hydraulic or ball bearing methods used to bend the main tubing), annealed, and washed in acid to remove oxides and flux from soldering. The valve cases are cut to length from heavy tubing and threaded at the ends. They then need to have holes cut into them that match those of the pistons. Even small manufacturers now have available computer programs that precisely measure where the holes should be drawn. The valve cases can be cut with drills whose heads are either pinpoint or rotary saws that cut the holes, after which pins prick out the scrap disk of metal. The knuckles, tubes and valve cases are then placed in jigs that hold them precisely, and their joints are painted with a solder and flux mixture using a blow torch. After an acid bath, the assembly is polished on a buffing machine, using wax of varying grittiness and muslin discs of varying roughness that rotate at high speeds (2,500 rpm is typical).

Assembly

5 The entire trumpet can now be assembled. The side tubes for the valve slides are joined to the knuckles and the main tubing is united end to end by overlapping their ferrules and soldering. Next, the pistons are then inserted, and the entire valve assembly is screwed onto the main tubing. The mouthpiece is then inserted.

6 The trumpet is cleaned, polished, and lacquered, or it is sent to be electroplated. The finishing touch is to engrave the name of the company on a prominent piece of tubing. The lettering is transferred to the metal with carbon paper, and a skilled engraver then carves the metal to match the etching.

7 Trumpets are shipped either separately for special orders or in mass quantities for high school bands. They are wrapped carefully in thick plastic bubble packaging or other insulating material, placed in heavy boxes full of insulation (such as packaging peanuts) then mailed or sent as freight to the customer.

Quality Control

The most important feature of a trumpet is sound quality. Besides meeting exacting tolerances of approximately 1 x 105 meters, every trumpet that is manufactured is tested by professional musicians who check the tone and pitch of the instrument while listening to see if it is in tune within its desired dynamic range. The musicians test-play in different acoustical set-ups, ranging from small studios to large concert halls, depending on the eventual use of the trumpet. Large trumpet manufacturers hire professional musicians as full-time testers, while small manufacturers rely on themselves or the customer to test their product.

At least half the work involved in creating and maintaining a clear-sounding trumpet is done by the customer. The delicate instruments require special handling, and, because of their inherent asymmetry, they are prone to imbalance. Therefore, great care must be taken so as not to carelessly damage the instrument. To prevent dents, trumpets are kept in cases, where they are held in place by trumpet shaped cavities that are lined with velvet. The trumpet needs to be lubricated once a day or whenever it is played. The lubricant is usually a petroleum derivative similar to kerosene for inside the valves, mineral oil for the key mechanism, and axle grease for the slides. The grime in the mouthpiece and main pipe should be cleaned every month, and every three months the entire trumpet should soak in soapy water for 15 minutes. It should then be scrubbed throughout with special small brushes, rinsed, and dried.

To maintain the life of the trumpet, it must occasionally undergo repairs. Large dents can be removed by locally annealing and hammering, small dents can be hammered out and balls passed through to test the final size, fissures can be patched, and worn pistons can be replated and ground back to their former size.

Where To Learn More

Books

Barclay, Robert. The Art of the Trumpet- Maker. Oxford University Press, Inc., 1992.

Bate, Philip. The Trumpet and Trombone. Ernest Benn, 1978.

Dundas, Richard J. Twentieth Century Brass Musical Instruments in the United States. Richard J. Dundas Publications, 1989.

Mueller, Kenneth A. Complete Guide to the Maintenance and Repair of Band Instruments. Parker Publishing, 1982.

Tarr, Edward. The Trumpet. Amadeus Press, 1988.

Tetzlaff, Daniel B. Shining Brass. Lemer Publications, 1963.

Tuckwell, Barry. Horn. Schirmer Books, 1983.

Whitener, Scott. A Complete Guide to Brass. Schirmer Books, 1990.

Periodicals

Benade, Arthur H. “How to Test a Good Trumpet.” The Instrumentalist. April, 1977, pp. 57-58.

“Yamaha Allows Players to Design Custom Trumpets,” Down Beat. December, 1991, p. 12.

Fasman, Mark J. “Brass Bibliography: Sources on the History, Literature, Pedagogy, Performance, and Acoustics of Brass Instruments,” rev. by Doug Rippey in RQ, Summer, 1991, p. 555.

Smithers, Don, Klaus Wogram, and John Bowsher. “Playing the Baroque Trumpet.” Scientific American. April, 1986, pp. 108¬115.

Weaver, James C. “The Trumpet Museum.” Antiques and Collecting Hobbies. January, 1990, p. 30.