Background

The umbrella as we know it today is primarily a device to keep people dry in rain or snow. Its original purpose was to shade a person from the sun (umbra is Latin for “shade”), a function that is still reflected in the word “parasol,” (derived from the French parare, “to shield” and sol, “sun”) a smaller-sized umbrella used primarily by women. There is an abundance of references to the usage of parasols and umbrellas in art and literature from ancient Africa, Asia, and Europe. For example, the Egyptian goddess Nut shielded the earth like a giant umbrella—only her toes and fingertips touched the ground—thus protecting humanity from the unsafe elements of the heavens. Although the Egyptians, like the Mesopotamians, used palm fronds and feathers in their umbrellas, they also introduced stretched papyrus as a material for the canopy, thereby creating a device that is recognizably an umbrella by modem standards.

About 2,000 years ago, the sun-umbrella was a common accessory for wealthy Greek and Roman women. It had become so identified as a “woman’s object” that men who used it were subjected to ridicule. In the first century A.D., Roman women took to oiling their paper sunshades, intentionally creating umbrellas for use in the rain. There is even a recorded lawsuit dating from the first century over whether women should be allowed to open umbrellas during events held in amphitheaters. Although umbrellas blocked the vision of those behind them, the women won their case.

It was not until 1750 that the Englishman Jonas Hanway set out to popularize the umbrella. Enduring laughter and scorn, Hanway carried an umbrella wherever he went; not only was the umbrella unusual, it was a threat to the coachmen of England, who derived a good portion of their income from gentlemen who took cabs in order to keep dry on rainy days. (In the late 1700s and early 1800s, another name for an umbrella was a “Hanway.”) Braving similar ridicule in 1778, John MacDonald, a well-known English gentlemen, carried an umbrella wherever he went.

Due to the efforts of Hanway, MacDonald, and other enterprising individuals, the umbrella became a common accessory. In nineteenth-century England, specially designed handles that concealed flasks for liquors, daggers and knives, small pads and pencils, or other items were in high demand by wealthy gentlemen. The umbrella became so popular that by the mid-twentieth century, if not earlier, etiquette demanded that the uniform of the English gentleman include hat, gloves, and umbrella.

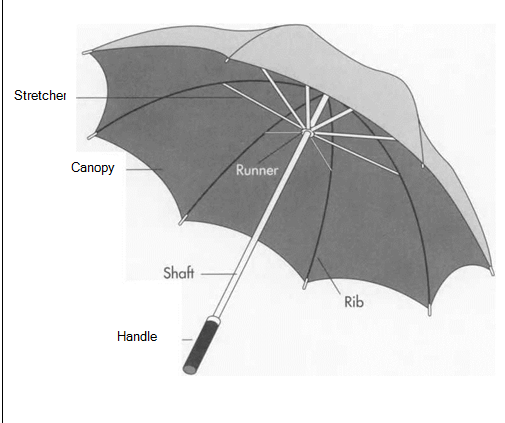

Among the qualities one might look for in an umbrella is the comfort of the handle, the ease with which the umbrella is opened and closed, and the closeness with which the canopy segments are connected to the ribs.

Raw Materials

Materials used to manufacture umbrellas have, of course, improved through the years. One of the most important innovations came in the early 1850s, when Samuel Fox conceived the idea of using “U” shaped steel rods for the ribs and stretchers to make a lighter, stronger frame. Previously, English umbrellas had been made from either cane or whalebone; whalebone umbrellas especially were bulky and awkward. Rounded ribs and stretchers are frequently seen today only on parasols and patio umbrellas. Advancements in metal-producing technology have made rounded metal ribs and stretchers more feasible, however, and some manufacturers produce umbrellas with these components. Modem rain umbrellas are made with fabrics (nylon, most commonly) that can withstand a drenching rain, dry quickly, fold easily, and are available in a variety of colors and designs.

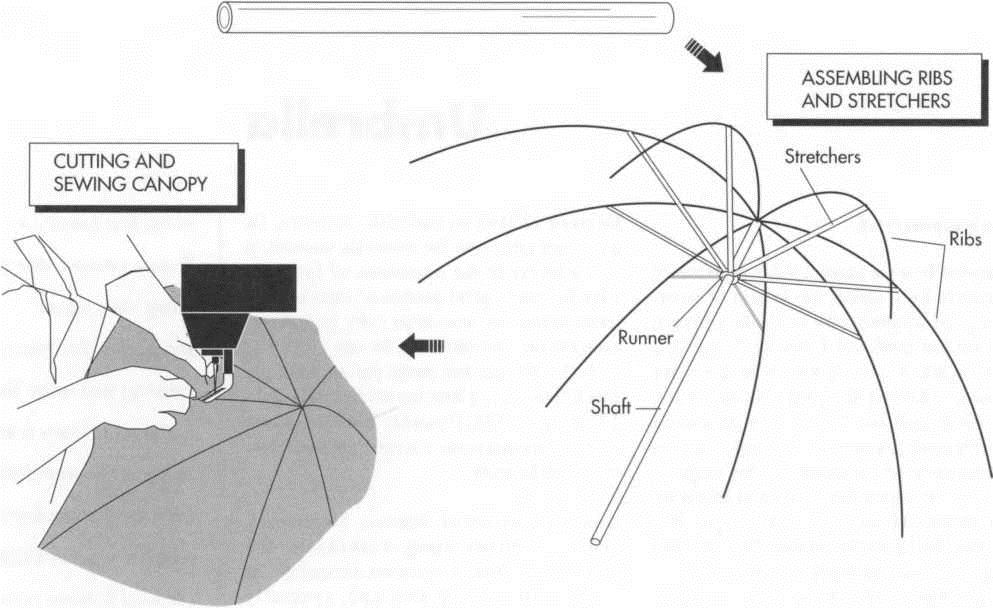

(Modern umbrellas are made by a hand-assembly process that, except for a few critical areas, can be done by semi-skilled workers. First, the shaft—whether wood, metal, or fiberglass—is made, and then the ribs and stretchers are assembled. Next, the nylon canopy is hand- sewn in sections (a typical umbrella has 8 sections).

The Manufacturing Process

Modern umbrellas are made by a hand- assembly process that, except for a few critical areas, can be done by semi-skilled workers. Choices of materials and quality control occur throughout the manufacturing process. Although a well-made umbrella need not be expensive, almost every purchasing decision impacts directly upon the quality of the final product.

Collapsible rain umbrellas that telescope into a length of about a foot are the most recent innovations in umbrellas. Though mechanically more complicated than stick umbrellas, they share the same basic technology. Among the differences between a stick umbrella and a collapsible umbrella is that the collapsible uses a two piece shaft that telescopes into itself, and an extra set of runners along the top of the umbrella. This section will focus on the manufacture of a stick umbrella.

The shaft

1 The stick umbrella will usually begin its life as a shaft of either wood, steel, or aluminum, approximately 3/8 inch (.95 centimeter) thick. Fiberglass and other plastics are occasionally used, and in fact they are common in the larger golf umbrella. Wood from various types of ash trees, including Rowan wood from Asia, is among the popular choices for a sturdy wood shaft. While wood shafts are made using standard wood- shaping machines such as turning machines and lathes, metal and plastic shafts can be drawn or extruded to the proper shape.

Ribs and stretchers

(The fabric for the canopy is usually a nylon taffeta with an acrylic coating on the underside and a scotch- guard type finish on the top. The coating and finish are usually applied by the fabric supplier. Other fabrics besides nylon might be used according to need or taste; a patio umbrella attached to an outdoor table does not have to be lightweight and waterproof as much as a customer might want it to be large, durable, and attractive.)

2 The ribs and stretchers are assembled first, usually from “U” shaped or channeled steel or other metal. Ribs run underneath the top or canopy of the umbrella; stretchers connect the ribs with the shaft of the umbrella. The ribs are attached to the shaft of the umbrella by fitting into a top notch—a thin, round nylon or plastic piece with teeth around the edges, and then held with thin wire. The stretchers are connected to the shaft of the umbrella with a plastic or metal runner, the piece that moves along the shaft of the umbrella when it is opened or closed.

3 Next, the ribs and stretchers are connected to each other with a joiner, which is usually a small jointed metal hinge; as the umbrella is opened or closed, the joiner opens or closes through an angle of more than 90 degrees.

4 There are two catch springs in the shaft of each umbrella; these are small pieces of metal that need to be pressed when the umbrella is slid up the shaft to open, and again when the umbrella is slid down the shaft for closing. Metal shafts are usually hollow, and the catch spring can be inserted, while a wood shaft requires that a space for the catch spring be hollowed out. A pin or other blocking device is usually placed into the shaft a few inches above the upper catch spring to prevent the canopy from sliding past the top of umbrella, when the runner goes beyond the upper catch spring.

Canopy

5 The cover or canopy of the umbrella is hand sewn in individual panels to the ribs. Because each panel has to be shaped to the curve of the canopy, the cover cannot be cut in one piece. Panels are sewn at the outer edges of the ribs, and there are also connections between the ribs and the panels about one-third of the way down from the outer rately from piles of materials called gores’, machine cutting of several layers at once is possible, although hand-cutting is more typical. The typical rain umbrella has eight panels, although some umbrellas with six panels (children’s umbrellas and parasols usually have six panels) and as many as twelve can occasionally be found. At one point, the number of panels in an umbrella may have been an indication of quality (or at least of the amount of attention the umbrella maker paid to his product). Today, because of the quality of the material available to the umbrella maker, the number of panels is usually a matter of style and taste rather than quality.

The fabric used in a good-quality umbrella canopy is usually a nylon taffeta rated at 190T (190 threads per inch), with an acrylic coating on the underside and a scotch-guard type finish on the top. The coating and finish are usually applied by the fabric supplier. Fabric patterns and designs can be chosen by the manufacturer, or the manufacturer might add his own patterns and designs using a rotary or silk screening process, especially for a special order of a limited number of umbrellas. Similarly, other fabrics besides nylon might be used according to need or taste; a patio umbrella attached to an outdoor table does not have to be lightweight and waterproof as much as a customer might want it to be large, durable, and attractive.

6 The tip of the umbrella that passes through the canopy can be covered with metal (a ferrule) that has been forced over and perhaps glued to the tip, or left bare, depending on the desire of the manufacturer. The handle is connected to the shaft at the end of the process, and can be wood, plastic, metal, or any combination of desired ingredients. Though handles can be screwed on, better quality umbrellas use glue to secure the handle more tightly.

7 The end tips of the umbrella, where the ribs reach past the canopy, can be left bare or covered with small plastic or wood end caps that are either pushed or screwed on, or glued, and then sewn to the ends of the ribs through small holes in the end caps.

8 Finally, the umbrella is packaged accordingly and sent to customers.

Where To Learn More

Books

Crawford, T. S. A History Of The Umbrella. Taplinger Publishing, 1970.

Stacey, Brenda. The Ups and Downs of Umbrellas. Alan Sutton Publishing, 1991.

Periodicals

“How to Choose a Good Umbrella,” Con¬sumer Reports. September, 1991, pp. 619-23.

“Nylon Ribs Toughen Umbrella Frame,” Design News. June 16, 1986, p. 49.

Jones, Arthur. “Personal Affairs—Sticks of Distinction,” Forbes. February 24, 1986, pp. 116-18.

Sedgwick, John. “Let It Pour: Getting a Handle on the Best Umbrella,” Gentlemen’s Quarterly. March, 1992, p. 51.

Shenker, Israel. “Yoicks! Yoicks! And Brolly Ho! Rah for the Parapluie!” Smithsonian. November, 1989, p. 130.