.jpg)

Background

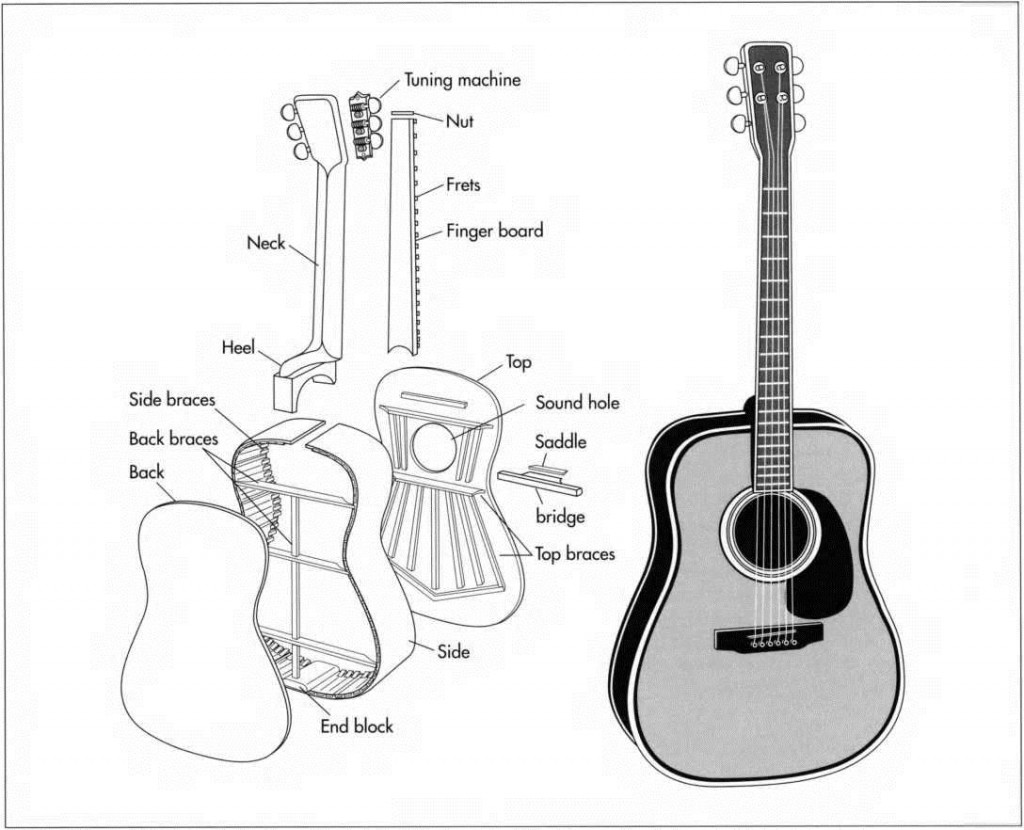

A member of the family of musical instruments called chordophones, the guitar is a stringed instrument with which sound is produced by “plucking” a series of strings running along the instrument’s body. While the strings are plucked with one hand, they are simultaneously fingered with the other hand against frets, which are metal strips located on the instrument’s neck. The subsequent sound is amplified through a resonating body. There are four general categories of acoustic (non-electric) guitars: flat-top steel- stringed, arched top, classic, and flamenco.

References to guitar-like instruments date back many centuries, and virtually every society throughout history has been found to have used a variation of the instrument. The forerunner of today’s guitars were single string bows developed during early human history. In sections of Asia and Africa, bows of this type have been unearthed in archaeological digs of ancient civilizations. Interestingly, one of these discoveries included an ancient Hittite carving—dating back more than 3,000 years—that depicted an instrument bearing many of the same features of today’s guitar: the curves of the body, a flat top with an incurred arc of five sound holes on either side, and a long fretted neck that ran the entire length of the body.

As music technology developed, more strings were added to the early guitars. A four-string variety (named guitarra latino) existed in Spain in the late thirteenth century. The guitarra latina closely resembled the ancient Hittite carving except that the instrument now included a bridge that held the strings as they passed over the sound hole. When a fifth string was added in the early sixteenth century, the guitar’s popularity exploded. A sixth string (bass E) was added near the end of 1700s, an evolution that brought the instrument closer to its present day functioning. The Carulli guitar of 1810 was one of the first to have six single strings tuned to notes in the present arrangement: E A D G B E.

Guitar technology finally made its way to the United States in the early nineteenth century, with Charles Friedrich Martin, a German guitar maker who emigrated to New York in 1833, leading the way. In the early 1900s, the Martin Company—now located in Nazareth, Pennsylvania—produced larger guitars that still adhered to the design of the classic models, especially the Spanish guitar. Another company, the Gibson company, followed suit and began to produce large steel-string guitars with arched fronts and backs. Known as the cello guitar, this brand of instrument produced a sound more suited for jazz and dance clubs. Another major innovation of the early 1900s was the use of magnetic pickups fitted beneath the strings by which sound traveled through a wire into an amplifier. These instruments would later evolve into electric guitars.

Raw Materials

The guitar industry is in virtual agreement on the woods used for the various parts of the instrument. The back and sides of the guitar’s body are usually built with East Indian or Brazilian rosewood. Historically, Brazilian rosewood has been the choice of connoisseurs. However, in an attempt to preserve the wood’s dwindling supply, the Brazilian goveminent has placed restrictions on its export, thus raising the price and making East Indian rosewood the current wood of choice. Less expensive brands use mahogany or maple, but the sound quality suffers in guitars constructed with those types of wood.

The top (or soundboard) of the guitar is traditionally constructed of Alpine spruce, although American Sika spruce has become popular among U.S. manufacturers. Cedar and redwood are often substituted for spruce, although these woods are soft and easily damaged during construction.

The neck, which must resist distortion by the pull of the strings and changes in temperature and humidity, is constructed from mahogany and joins the body between the fourteenth and twelfth frets. Ideally, the fingerboard is made of ebony, but rosewood is often used as a less expensive alternative. Most modern guitars use strings made of some type of metal (usually steel).

(Guitar manufacture generally involves selecting, sawing, and glueing various wood pieces to form tfie finished instrument. The top and back of the guitar are formed in a process known as “book matching,” by which a single piece of wood is sliced into two sheets, each the same length and width as the original but only half as thick. This gives the sheets a symmetrical grain pattern. The two sheets are matched to ensure continuity in the grains and glued together.)

The Manufacturing Process

The first and most important step in guitar construction is wood selection. The choice of wood will directly affect the sound quality of the finished product. The wood must be free of flaws and have a straight, vertical grain. Since each section of the guitar uses different types of woods, the construction process varies from section to section. Following is a description of the manufacture of a typical acoustic guitar.

Book matching

1 The wood for the top of the guitar is cut from lumber using a process called book- matching. Book matching is a method by which a single piece of wood is sliced into two sheets, each the same length and width as the original but only half as thick. This gives the sheets a symmetrical grain pattern. The two sheets are matched to ensure continuity in the grains and glued together. Once dry, the newly joined boards are sanded to the proper thickness. They are closely inspected for quality and then graded according to color, closeness and regularity of grain, and lack of blemishes.

2 The next step is to cut the top into the guitar shape, leaving the piece of wood oversized until the final trimming. The sound hole is sawed, with slots carved around it for concentric circles that serve as decorative inlays around the sound hole.

Strutting

3 Wood braces are next glued to the under-side of the top piece. Strutting, as this process is often called, serves two purposes: brace the wood against the pull of the strings and control the way the top vibrates. An area of guitar construction that differs from company to company, strutting has a great affect on the guitar’s tone. Many braces today are glued in an X-pattem originally designed by the Martin Company, a pattern that most experts feel provides the truest acoustics and tone. Although companies such as Ovation and Gibson continue to experiment with improvements on the X-pattem style of strutting, Martin’s original concept is widely accepted as producing the best sound.

4 The back, although not as acoustically important as the top, is still critical to the guitar’s sound. A reflector of sound waves, the back is also braced, but its strips of wood run parallel from left to right with one cross grained strip running down the length of the back’s glue joint. The back is cut and glued similar to the top—and from the same piece of lumber as the top, to ensure matching grains—using the book match technique.

Constructing the sides

5 Construction of the sides consists of cutting and sanding the strips of wood to the proper length and thickness and then softening the wood in water. The strips are then placed in molds that are shaped to the curves of the guitar, and the entire assembly is clamped for a period of time to ensure symmetry between the two sides. The two sides are joined together with basswood glued to the inside walls. Strips of reinforcing wood are placed along the inner sides so that the guitar doesn’t crack if hit from the side. Two end blocks (near the neck and near the bottom of the guitar) are also used to join the top, back and neck.

6 Once the sides are joined and the end-blocks are in place, the top and the back are glued to the sides. The excess wood is trimmed off and slots are cut along the side- top and side-back junctions. These slots are for the body bindings that cover the guitar’s sides. The bindings are not only decorative, they also keep moisture from entering through the sides and warping the guitar.

Neck and fingerboard

7 The neck is made from one piece of hard wood, typically mahogany or rosewood, carved to exact specifications. A reinforcing rod is inserted through the length of the neck and, after sanding, the fingerboard (often made of ebony or rosewood) is set in place. Using precise measurements, fret slots are cut into the fingerboard and the steel-wired frets are put in place.

8 Once the neck construction is completed, it is attached to the body. Most guitar companies attach the neck and the body by fitting a heel that extends from the base of the neck into a pre-cut groove on the body. Once the glue has dried at the neck-body junction, the entire guitar receives a coat of sealer and then several coats of lacquer. On some models, intricate decorations or inlays are also placed on the guitar top.

Bridge and saddle

9 After polishing, a bridge is attached near the bottom of the guitar below the sound-hole, and a saddle is fitted. The saddle is where the strings actually lie as they pass over the bridge, and it is extremely important in the transferring of string vibration to the guitar top. On the opposite end of the guitar, the nut is placed between the neck and the head. The nut is a strip of wood or plastic on which the strings lie as they pass to the head and into the tuning machine.

Tuning machine

The tuning machine is next fitted to the guitar head. This machine is one of the most delicate parts of the guitar and is usually mounted on the back of the head. The pegs that hold each string poke through to the front, and the gears that turn both the pegs and the string-tightening keys are housed in metal casings.

Finally, the guitar is strung and inspected before leaving the factory. The entire process of making a guitar can take between three weeks and two months, depending on the amount of decorative detail work on the guitar top.

Electric Guitars

A separate but closely related group of guitars is the electric guitar, which uses a device known as a pickup—a magnet surrounded by wire—to convert the energy from string vibrations into an electrical signal. The signal is sent to an amplifier, where it is boosted thousands of times. The body of an electric guitar has little impact on the quality of sound produced, as the amplifier controls both the quality and loudness of the sound. Acoustic guitars can also be fitted with electric pickups, and there are some models available today that already have the pickup built into the body.

Quality Control

Most guitar manufacturers are small, highly personal companies that stress detail and quality. Each company does its own research and testing, which virtually insure the customer of a flawless guitar. During the past few decades, the guitar industry has become more mechanized, allowing for greater speed, higher consistency and lower pricing. Although purists resist mechanization, a well-trained workman using machine tools can usually produce a higher-quality instrument than a craftsman working alone. The final testing procedures at most manufactures are quite stringent; only the best guitars leave the plant, and more than one person makes the final determination as to which instruments are shipped out and which are rejected.

Where To Learn More

Books

Cumpiano, William R. Guitarmaking: Tradi¬tion & Technology. Rosewood Press, 1987.

Evans, Tom and Mary Anne. Guitars: Music, History, Construction and Players from the Renaissance to Rock. Facts on File, 1977.

Hill, Thomas. The Guitar: An Introduction to the Instrument. Watts Publishing, 1973.

How It Works: The Illustrated Science and Invention Encyclopedia. Vol. 9. H. S. Stuttman, 1983.

Kamimoto, Hideo. Complete Guitar Repair. Oak Publications, 1975.

Wheeler, Thomas. The Guitar Book. Harper &Row, 1974.

Periodicals

Del Ray, Tiesco. “Off the Wall: The Theory of Reverse Ergonomics,” Guitar Player. March, 1986, p. 102.

Sievert, Jon. “Steinberger Factory Tour,” Guitar Player. December, 1988, p. 38.

Smith, Richard. “Inside Rickenbacker: New Factory, Old Traditions,” Guitar Player. February, 1990, p. 61.

Widders-Ellis, Andy. “Tomorrow’s Acoustics: The Dawning of a New Golden Age,” Guitar Player. April, 1992, p. 43.