Background

Coffee is a beverage made by grinding roasted coffee beans and allowing hot water to flow through them. Dark, flavorful, and aromatic, the resulting liquid is usually served hot, when its full flavor can best be appreciated. Coffee is served internationally—with over one third of the world’s population consuming it in some form, it ranks as the most popular processed beverage— and each country has developed its own preferences about how to prepare and present it. For example, coffee drinkers in Indonesia drink hot coffee from glasses, while Middle Easterners and some Africans serve their coffee in dainty brass cups. The Italians are known for their espresso, a thick brew served in tiny cups and made by dripping hot water over twice the normal quantity of ground coffee, and the French have contributed café au lait, a combination of coffee and milk or cream which they consume from bowls at breakfast.

A driving force behind coffee’s global popularity is its caffeine content: a six-ounce (2.72 kilograms) cup of coffee contains 100 milligrams of caffeine, more than comparable amounts of tea (50 milligrams), cola (25 milligrams), or cocoa (15 milligrams). Caffeine, an alkaloid that occurs naturally in coffee, is a mild stimulant that produces a variety of physical effects. Because caffeine stimulates the cortex of the brain, people who ingest it experience enhanced concentration. Athletes are sometimes advised to drink coffee prior to competing, as caffeine renders skeletal muscles less susceptible to exhaustion and improves coordination. However, these benefits accrue only to those who consume small doses of the drug.

Excessive amounts of caffeine produce a host of undesirable consequences, acting as a diuretic, stimulating gastric secretions, upsetting the stomach, contracting blood vessels in the brain (people who suffer from headaches are advised to cut their caffeine intake), and causing over acute sensation, irregular heartbeat, and trembling. On a more serious level, many researchers have sought to link caffeine to heart disease, benign breast cysts, pancreatic cancer, and birth defects. While such studies have proven inconclusive, health official nonetheless recommend that people limit their coffee intake to fewer than four cups daily or drink decaffeinated varieties.

Coffee originated on the plateaus of central Ethiopia. By A.D. 1000, Ethiopian Arabs were collecting the fruit of the tree, which grew wild, and preparing a beverage from its beans. During the fifteenth century traders transplanted wild coffee trees from Africa to southern Arabia. The eastern Arabs, the first to cultivate coffee, soon adopted the Ethiopian Arabs’ practice of making a hot beverage from its ground, roasted beans.

The Arabs’ fondness for the drink spread rapidly along trade routes, and Venetians had been introduced to coffee by 1600. In Europe as in Arabia, church and state officials frequently proscribed the new drink, identifying it with the often-liberal discussions conducted by coffee house habitués, but the institutions nonetheless proliferated, nowhere more so than in seventeenth-century London. The first coffee house opened there in 1652, and a large number of such establishments {cafés) opened soon after on both the European continent (café derives from the French term for coffee) and in North America, where they appeared in such Eastern cities as New York, Boston, and Philadelphia in the last decade of the seventeenth century.

In the United States, coffee achieved the same, almost instantaneous popularity that it had won in Europe. However, the brew favored by early American coffee drinkers tasted significantly different from that enjoyed by today’s connoisseurs, as nineteenth-century cookbooks make clear. One 1844 cookbook instructed people to use a much higher coffee/water ratio than we favor today (one tablespoon per sixteen ounces); boil the brew for almost a half an hour (today people are instructed never to boil coffee); and add fish skin, isinglass (a gelatin made from the air bladders of fish), or egg shells to reduce the acidity brought out by boiling the beans so long (today we would discard overly acidic coffee). Coffee yielded from this recipe would strike modem coffee lovers as intolerably strong and acidic; moreover, it would have little aroma.

American attempts to create instant coffee began during the mid-1800s, when one of the earliest instant coffees was offered in cake form to Civil War troops. Although it and other early instant coffees tasted even worse than regular coffee of the epoch, the incentive of convenience proved strong, and efforts to manufacture a palatable instant brew continued. Finally, after using U.S. troops as testers during World War II, an American coffee manufacturer (Maxwell House) began marketing the first successful instant coffee in 1950.

At present, 85 percent of Americans begin their day by making some form of the drink, and the average American will consume three cups of it over the course of the day.

Raw Materials

Coffee comes from the seed, or bean, of the coffee tree. Coffee beans contain more than 100 chemicals including aromatic molecules, proteins, starches, oils, and bitter phenols (acidic compounds), each contributing a different characteristic to the unique flavor of coffee. The coffee tree, a member of the evergreen family, has waxy, pointed leaves and jasmine-like flowers. Actually more like a shrub, the coffee tree can grow to more than 30 feet (9.14 meters) in its wild state, but in cultivation it is usually trimmed to between five and 12 feet (1.5 and 3.65 meters). After planting, the typical tree will not produce coffee beans until it blooms, usually about five years. After the white petals drop off, red cherries form, each with two green coffee beans inside. (Producing mass quantities of beans requires a large number of trees: in one year, a small bush will yield only enough beans for a pound of coffee.) Because coffee berries do not ripen uniformly, careful harvesting requires picking only the red ripe berries: including unripened green ones and overly ripened black ones will affect the coffee taste.

Coffee trees grow best in a temperate climate without frost or high temperatures. They also seem to thrive in fertile, well-drained soil; volcanic soil in particular seems conducive to flavorful beans. High altitude plantations located between 3,000 and 6,000 feet (914.4 and 1,828.8 meters) above sea level produce low-moisture beans with more flavor. Due to the positive influences of volcanic soil and altitude, the finest beans are often cultivated in mountainous regions. Today, Brazil produces about half of the world’s coffee. One quarter is produced elsewhere in Latin America, and Africa contributes about one sixth of the global supply.

Currently, about 25 types of coffee trees exist, the variation stemming from environmental factors such as soil, weather, and altitude. The two main species are coffea robusta and coffea arabica. The robusta strain produces less expensive beans, largely because it can be grown under less ideal conditions than the arabica strain. When served, coffee made from arabica beans has a deep reddish cast, whereas robusta brews tend to be dark brown or black in appearance. The coffees made from the two commonly used beans differ significantly. Robusta beans are generally grown on large plantations where the berries ripen and are harvested at one time, thereby increasing the percentage of under- and overripe beans. Arabica beans, on the other hand, comprise the bulk of the premium coffees that are typically sold in whole bean form so purchasers can grind their own coffee. Whether served in a coffee house or prepared at home, coffee made from such beans offers a more delicate and less acidic flavor.

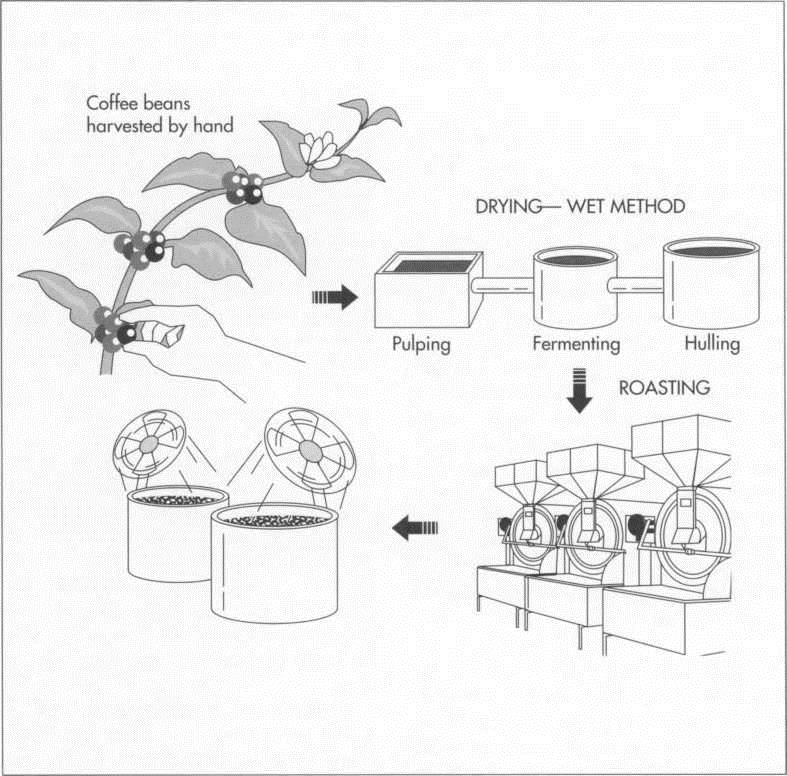

(Coffee bean harvesting is still done manually. The beans grow in clusters of two; each cluster is called a “cherry.” Next, the beans are dried and husked. In one method, the wet method, the beans are put in pulping machines to remove most of the husk. After fermenting in large tanks, the beans are put in hulling machines, where mechanical stirrers remove the final covering and polish the beans to a smooth, glossy finish. After being cleaned and sorted, the beans are roasted in huge ovens. Only after roasting do the beans emit their familiar aroma. The beans are then cooled.)

The Manufacturing Process

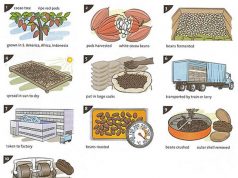

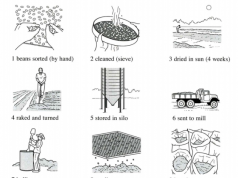

Drying and husking the cherries

1 First, the coffee cherries must be harvested, a process that is still done manually. Next, the cherries are dried and husked using one of two methods. The dry method is an older, primitive, and labor-intensive process of distributing the cherries in the sun, raking them several times a day, and allowing them to dry. When they have dried to the point at which they contain only 12 percent water, the beans’ husks become shriveled. At this stage they are hulled, either by hand or by a machine.

2 In employing the wet method, the hulls are removed before the beans have dried. Although the fruit is initially processed in a pulping machine that removes most of the material surrounding the beans, some of this glutinous covering remains after pulping.

This residue is removed by letting the beans ferment in tanks, where their natural enzymes digest the gluey substance over a period of 18 to 36 hours. Upon removal from the fermenting tank, the beans are washed, dried by exposure to hot air, and put into large mechanical stirrers called hullers. There, the beans’ last parchment covering, the pergamino, crumbles and falls away easily. The huller then polishes the bean to a clean, glossy finish.

Cleaning and grading the beans

3 The beans are then placed on a convey or belt that carries them past workers who remove sticks and other debris. Next, they are graded according to size, the location and altitude of the plantation where they were grown, drying and husking methods, and taste. All these factors contribute to certain flavors that consumers will be able to select thanks in part to the grade.

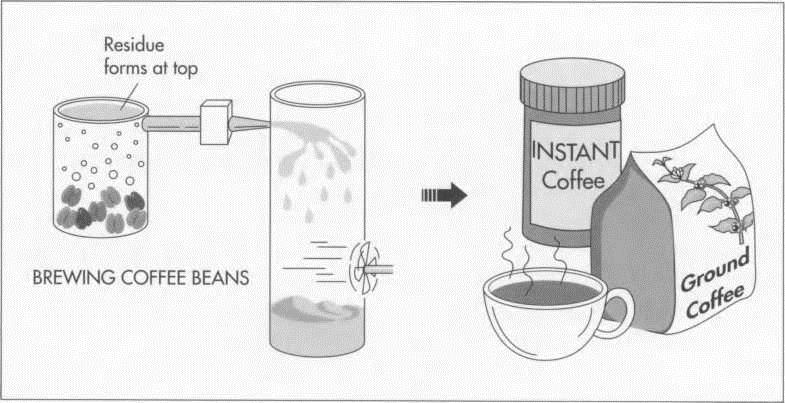

(To make instant coffee, manufacturers grind the beans and brew the mixture in percolators. During this process, an extract forms and is sprayed into a cylinder. As it travels down the cylinder, the extract passes through warm air that converts it into a dry powder)

4 Once these processes are completed, workers select and pack particular types and grades of beans to fill orders from the various roasting companies that will finish preparing the beans. When beans (usually robusta) are harvested under the undesirable conditions of hot, humid countries or coastal regions, they must be shipped as quickly as possible, because such climates encourage insects and fungi that can severely damage a shipment.

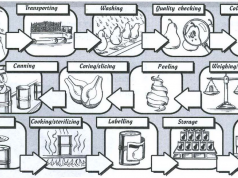

5 When the coffee beans arrive at a roasting plant, they are again cleaned and sorted by mechanical screening devices to remove leaves, bark, and other remaining debris. If the beans are not to be decaffeinated, they are ready for roasting.

Decaffeinoting

If the coffee is to be decaffeinated, it is now processed using either a solvent or a water method. In the first process, the coffee beans are treated with a solvent (usually methylene chloride) that leaches out the caffeine. If this decaffeination method is used, the beans must be thoroughly washed to remove traces of the solvent prior to roasting. The other method entails steaming the beans to bring the caffeine to the surface and then scraping off this caffeine-rich layer.

Roasting

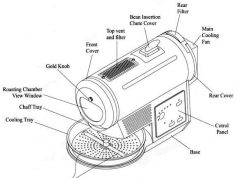

7 The beans are roasted in huge commercial roasters according to procedures and specifications which vary among manufacturers (specialty shops usually purchase beans directly from the growers and roast them on-site). The most common process entails placing the beans in a large metal cylinder and blowing hot air into it. An older method, called singeing, calls for placing the beans in a metal cylinder that is then rotated over an electric, gas, or charcoal heater.

Regardless of the particular method used, roasting gradually raises the temperature of the beans to between 431 and 449 degrees Fahrenheit (220-230 degrees Celsius). This triggers the release of steam, carbon monoxide, carbon dioxide, and other volatiles, reducing the weight of the beans by 14 to 23 percent. The pressure of these escaping internal gases causes the beans to swell, and they increase their volume by 30 to 100 percent. Roasting also darkens the color of the beans, gives them a crumbly texture, and triggers the chemical reactions that imbue the coffee with its familiar aroma (which it has not heretofore possessed).

8 After leaving the roaster, the beans are placed in a cooling vat, wherein they are stirred while cold air is blown over them. If the coffee being prepared is high-quality, the cooled beans will now be sent through an electronic sorter equipped to detect and eliminate beans that emerged from the roasting process too light or too dark.

9 If the coffee is to be pre-ground, the manufacturer mills it immediately after roasting. Special types of grinding have been developed for each of the different types of coffee makers, as each functions best with coffee ground to a specific fineness.

Instant coffee

10 If the coffee is to be instant, it is brewed with water in huge percolators after the grinding stage. An extract is clarified from the brewed coffee and sprayed into a large cylinder. As it falls downward through this cylinder, it enters a warm air stream that converts it into a dry powder.

Packaging

Because it is less vulnerable to flavor and aroma loss than other types of coffee, whole bean coffee is usually packaged in foil-lined bags. If it is to retain its aromatic qualities, pre-ground coffee must be hermetically sealed: it is usually packaged in impermeable plastic film, aluminum foil, or cans. Instant coffee picks up moisture easily, so it is vacuum-packed in tin cans or glass jars before being shipped to retail stores.

Environmental Concerns

Methylene chloride, the solvent used to decaffeinate beans, has come under federal scrutiny in recent years. Many people charge that rinsing the beans does not completely remove the chemical, which they suspect of being harmful to human health. Although the Food and Drug Administration has consequently ruled that methylene chloride residue cannot exceed 10 parts per million, the water method of decaffeination has grown in popularity and is expected to replace solvent decaffeination completely.

Where To Learn More

Books

Davids, Kenneth. Coffee. 101 Productions, 1987.

Pamphlets

“More Fun With Coffee.” National Coffee Association.

“The Story of Good Coffee from the Pacific Northwest.” Starbucks Coffee Company.

Periodicals

“From Tree to Bean to Cup,” Consumer Reports. September, 1987, p. 531.

Globus, Paul. “This Little bean is Big Business,” Reader’s Digest (Canadian), March, 1986, p. 35.