Background

Wild peanuts originated in Bolivia and north-eastern Argentina. The cultivated species, Arachis hypogaea, was grown by Indians in pre-Columbian times. The peanut plant is a vine like plant whose flowers talks wither and bow to the ground after fertilization, burying the young pods, which come to maturity underground.

Peanuts were introduced to the United States from Africa, but were not considered a staple crop until the 1890s, when they were promoted as a replacement for the cotton crop destroyed by the boll weevil.

The three types of domestic peanuts are the Virginia, Spanish, and Runner-type peanuts. It is mostly the Runner-type peanuts, grown in Alabama, Florida, and Georgia, that are used in the manufacture of peanut butter. While Runner peanuts offer a higher yield, they also require more moisture than the Spanish or Virginia peanuts.

Around the end of the seventeenth century, Haitians made peanut butter by using a heavy wood mortar and a wood pestle with a metal cap. The mortar—featuring a metal bottom and weighing about 20 pounds—and the 5- pound pestle were used to pound the peanuts into a paste. During the nineteenth century in the United States, shelled, roasted peanuts were chopped or pounded into a creamy paste in a cloth bag and eaten fresh. American botanist and inventor George Washington Carver experimented with soybeans, sweet potatoes, and other crops, eventually deriving 300 products from the peanut alone—among the most notable was peanut butter.

A physician in St. Louis, Missouri started manufacturing peanut butter commercially in 1890. Featured at the St. Louis World’s Fair as a health food, peanut butter was recommended for infants and invalids because of its high nutritional value. Sanitariums, particularly one in Battle Creek, Michigan, used it for their patients because of its high protein content.

Around 1925, peanut butter was sold from an open tub, with half an inch of oil on the surface. While the paste was sticky and produced considerable thirst, consumers were ready for such an economical and nutritious staple.

Realizing that the financial rewards from pig feed were beginning to dwindle, farmers began investing in the new cash crop. Thus, with increased harvest and availability of peanuts, the development and production of peanut butter grew. Most recently, peanut butter has been used primarily as a sandwich spread, although it also appears in prepared dishes and confections.

Originally, the process of peanut butter manufacturing was entirely manual. Until about 1920, the peanut farmer shelled the seed by hand, cultivated by hand hoeing about four times, and plowed with a single furrow plow, also four times. The farmer dug the vines with a single row plow, manually stacked the vines in the field for drying, and then hand- picked the nuts or beat them from the vines. A mule, a plow, and two hoes were all that was needed as far as peanut cultivation equipment was concerned. To produce peanut butter, small batches of peanuts were roasted, blanched, and ground as needed for sale or consumption. Salt and/or sugar was added upon request, and the product was eaten fresh. Mechanized cultivation and harvesting increased the yield of the harvest. Milling plants became larger, and consumption soared.

Raw Materials

The peanut, rich in fat, protein, vitamin B, phosphorus, and iron, has significant food value. In its final form, peanut butter consists of about 90 to 95 percent carefully selected, blanched, dry-roasted peanuts, ground to a size to pass through a 200-mesh screen. To improve smoothness, spread ability and flavor, other ingredients are added, including include salt (1.5 percent), hydrogenated vegetable oil (0.125 percent), dextrose (2 percent), and com syrup or honey (2 to 4 percent). To enhance peanut butter’s nutritive value, ascorbic acid and yeast are also added. The amounts of other ingredients can vary as long as they do not add up to more than 10 percent of the peanut butter. Peanut butter contains 50 to 52 percent fat, 28 to 29 percent protein, 2 to 5 percent carbohydrate, and 1 to 2 percent moisture.

The Manufacturing Process

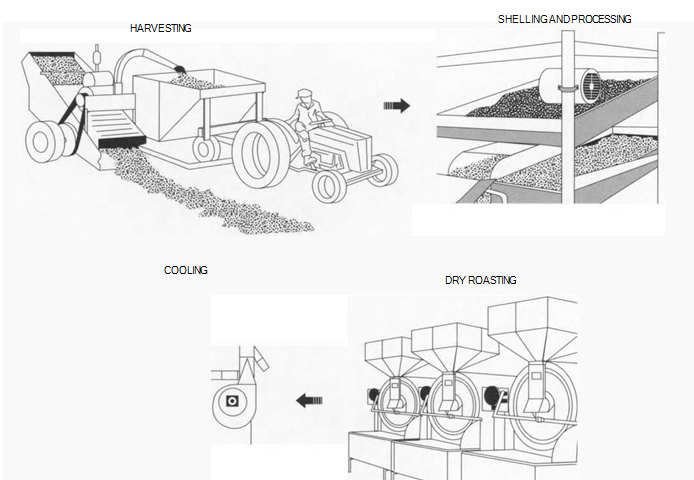

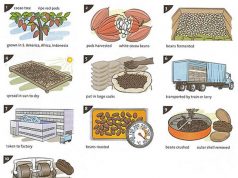

Planting and harvesting peanuts

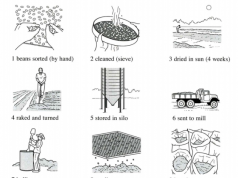

1 Peanuts are planted in April or May, depending upon the climate. The peanut emerges as a plant followed by a yellow flower. After blooming and then wilting, the flower bends over and penetrates the soil. The peanut is formed underground. Peanuts are harvested beginning in late August, but mostly in September and October, during clear weather, when the soil is dry enough so it wifl not adhere to the stems and pods. The peanuts are removed from vines by portable, mechanical pickers and transported to a peanut sheller for mechanical drying.

2 Peanuts from the pickers are delivered to warehouses for cleaning. Blowers remove dust, sand, vines, stems, leaves, and empty shells. Screens, magnets, and size graders re- move trash, metal, rocks, and clods. After the cleaning process, the peanuts weigh 10 to 20 percent less. The raw, cleaned peanuts are stored unshelled in silos or warehouses.

Shelling and processing

3 Shelling consists of removing the shell (or hull) of peanuts with the least damage to the seed or kernels. The moisture of the unshelled peanuts is adjusted to avoid excessive brittleness of the shells and kernels and to reduce the amount of dust in the plant. The size-graded peanuts are passed between a series of rollers adjusted to the variety, size, and condition of the peanuts, where the peanuts are cracked. The cracked peanuts then repeatedly pass over screens, sleeves, blowers, magnets, and destoners, where they are shaken, gently tumbled, and air blown, until all the shells and other foreign material (rocks, mudballs, metal, shrivels) are removed.

(The first several steps in peanut butter manufacture involve processing the main ingredient: the peanuts. After harvesting, the peanuts are cleaned, shelled, and graded for size. Next, they are dry roasted in large ovens, and then they are transferred to cooling machines, where suction fans draw cooling air over the peanuts)

4 The shelled peanuts are graded for size in a size grader. The peanuts are lifted and then oriented on the perforations of the size grader. The larger peanuts (the “overs”) are sent to one trough, while the “troughs” are guided towards another trough. The peanuts are then graded for color, defects, spots, and broken skins.

5 The peanuts are shipped in large bulk containers or sacks to peanut butter manufacturers. (Inedible peanuts are diverted as oil stock in semibulk form.) To ensure proper size and grading, the truckloads transporting peanuts to peanut manufacturers are sampled mechanically. The sampler, testing two truckloads simultaneously, can quickly and accurately assess size and grading by examining 10 samples per truckload. If edible peanuts need to be stored for more than 60 days, they are placed in refrigerated storage at 34 to 40 degrees Fahrenheit (2 to 6 degrees Celsius), where they may be held for as long as 25 months. Shelled, the remaining peanuts weigh 30 to 60 percent less, occupy 60 to 70 percent less space, and have a shelf life about 60 to 75 percent shorter than unshelled peanuts.

(After tfie peanuts are roasted and cooled, they undergo blanching— removal of the skins by heat or water. The heat method has the advantage of removing the bitter heart of the peanut. Next, the blanched peanuts are pulverized and ground with salt, dextrose, and hydrogenated oil stabilizer in a grinding machine. After cooling, the peanut butler is ready to be packaged.)

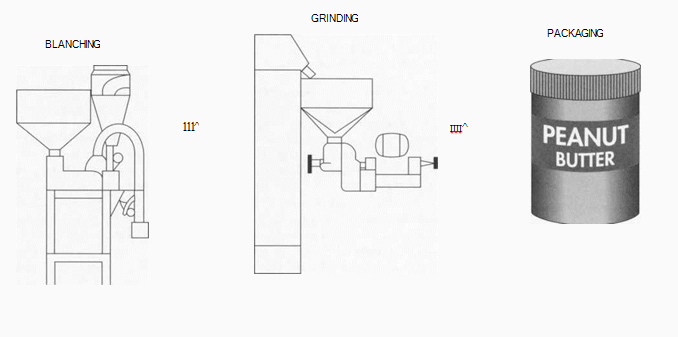

The peanut butter manufacturers first dry roast the peanuts. Dry roasting is done by either the batch or continuous method. In the batch method, peanuts are roasted in 400-pound lots in a revolving oven heated to about 800 degrees Fahrenheit (426.6 degrees Celsius). The peanuts are heated at 320 degrees Fahrenheit (160 degrees Celsius) and held at this temperature for 40 to 60 minutes to reach the exact degree of doneness. All the nuts in each batch must be uniformly roasted.

Large manufacturers prefer the continuous method, in which peanuts are fed from the hopper, roasted, cooled, ground into peanut butter and stabilized in one operation. This method is less labor-intensive, creates a more uniform roasting, and decreases spillage. Still, some operators believe that the best commercial peanut butter is obtained by using the batch method. Since peanut butter may call for a blending of peanuts, the batch method allows for the different varieties to be roasted separately. Furthermore, since peanuts frequently come in lots of different moisture content which may need special attention during roasting, the batch method can also meet these needs readily. The steps outlined below apply to peanut butter manufacturing that uses the batch method of roasting.

Cooling and blanching

7 A photometer indicates when the cooking is complete. At the exact time cooking is completed, the roasted peanuts are removed from heat as quickly as possible in order to stop cooking and produce a uniform product. The hot peanuts then pass from the roaster directly to a perforated metal cylinder (or blower-cooler vat), where a large volume of air is pulled through the mass by suction fans. The peanuts are brought to a temperature of 86 degrees Fahrenheit (30 degrees Celsius). Once cooled, the peanuts pass through a gravity separator that removes foreign materials.

8 The skins (or seed coats) are now removed with either heat or water. The heat blanching method has the advantage of removing the hearts of the peanuts, which contain a bitter principle.

Heat blanching: Depending on the variety and degree of doneness desired, the peanuts are exposed to a temperature of 280 degrees Fahrenheit (137.7 degrees Celsius) for up to 20 minutes to loosen and crack the skins. After cooling, the peanuts are passed through the blancher in a continuous stream and subjected to a thorough but gentle rubbing between brushes or ribbed rubber belting. The skins are rubbed off, blown into porous bags, and the hearts are separated by screening.

Water blanching: A newer process than heat blanching, water blanching was introduced in 1949. While the kernels are not heated to destroy natural antioxidants, drying is necessary in this process and the hearts are retained. The first step is to arrange the kernels in troughs, then roll them between sharp stationary blades to slit the skins on opposite sides. The skins are removed as a spiral conveyor carries the kernels through a one-minute scalding water bath and then under an oscillating canvas-covered pad, which rubs off their skins. The blanched kernels are then dried for at least six hours by a current of 120 degrees Fahrenheit (48.8 degrees Celsius) air.

9 The blanched nuts are mechanically screened and inspected on a conveyor belt to remove scorched and rotten nuts or other undesirable matter. Light nuts are removed by blowers, discolored nuts by a high-speed electric color sorter, and metal parts by magnets.

Grinding

Most of the devices used for grinding peanuts into butter are built so they can be adjusted over a wide range—permitting the variation in the quantity of peanuts ground per hour, the fineness of the product, and the amount of oil freed from the peanuts. Most grinding mills also have an automatic feed for peanuts and salt, and are easy to clean. To prevent overheating, grinding mills are cooled by a water jacket.

Peanut butter is usually made by two grinding operations. The first reduces the nuts to a medium grind and the second to a fine, smooth texture. For fine grinding, clearance between plates is about .032 inch (.08 centimeter). The second milling uses a very high-speed comminutor that has a combination cutting-shearing and attrition action and operates at 9600 rpm. This milling produces a very fine particle with a maximum size of less than 0.01 inch (.025 centimeter). To make chunky peanut butter, peanut pieces approximately the size of one-eighth of a kernel are mixed with regular peanut butter, or incomplete grinding is used by removing a rib from the grinder.

At the same time the peanuts are fed into the grinder to be milled, about 2 percent salt, dextrose, and hydrogenated oil stabilizer are fed into the grinder in a continuous, horizontal operation, with about plus or minus 2 percent accuracy, and are thoroughly dispersed.

Peanuts are kept under constant pressure from the start to the finish of the grinding process to assure uniform grinding and to protect the product from air bubbles. A heavy screw feeds the peanuts into the grinder. This screw may also deliver the deaerated peanut butter into containers in a continuous stream under even pressure. From the grinder, the peanut butter goes to a stainless steel hopper, which serves as an intermediate mixing and storage point. The stabilized peanut butter is cooled in this rotating refrigerated cylinder (called a votator), from 170 to 120 degrees Fahrenheit (76.6 to 48.8 degrees Celsius) or less before it is packaged.

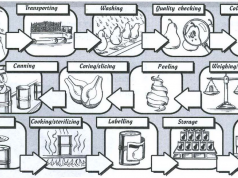

Packaging

1 O The stabilized peanut butter is automatically packed in jars, capped, and labeled. Since proper packaging is the main factor in reducing oxidation (without oxygen no oxidation can occur), manufacturers use vacuum packing. After it is put into final containers, the peanut butter is allowed to remain undisturbed until crystallization throughout the mass is completed. Jars are then placed in cartons and placed in product storage until ready to be shipped out to retail or institutional customers.

Quality Control

Quality control of peanut butter starts on the farm through harvesting and curing, and is then carried through the steps of shelling, storing, and manufacturing the product. All these steps are handled by machines. While complete mechanical harvesting, curing, and shelling may have some disadvantages, the end result is a brighter, cleaner, and more uniform peanut crop.

In the United States, strict quality control has been maintained on peanuts for many years with cooperation and approval from both the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) and the Food and Drug Administration (FDA). Quality control is handled by the Peanut Administrative Committee, which is an arm of the USDA. Raw peanut responsibility rests with the Department of Agriculture. During and after manufacture, quality control is under the supervision of the FDA.

In its definition of peanut butter, the FDA stipulates that seasoning and stabilizing ingredients must not “exceed 10 percent of the weight of the finished food.” Furthermore, the FDA states that “artificial flavorings, artificial sweeteners, chemical preservatives, added vitamins, and color additives are not suitable ingredients of peanut butter.” A product that does not conform to the FDA’s standards must be labeled “imitation peanut butter.”

Byproducts

Peanut vines and leaves are used for feed for cattle, sheep, goats, horses, mules, and other livestock because of high nutritional value. Peanut shells accumulate in great quantities at shelling plants. They contain stems, peanut pops, immature nuts and dirt. These shells are used mainly for fuel for the boiler generating steam for making electricity to operate the shelling plant. Limited markets exist for peanut shells for roughage in cattle feed, poultry litter, and filler in artificial fire logs. Potential additional uses are pet litter, mush-room-growing medium, and floor-sweeping compounds.

The Future

In the United States and most of the 53 peanut-producing countries in the world, the production and consumption of peanuts, including peanut butter, is increasing. The quality of peanuts continues to improve to meet higher standards. The convenience peanut butter offers its users and its high nutritional value meet the demands of contemporary lifestyles.

The use of peanuts as food is being introduced to remote parts of the world by American ambassadors, missionaries and Peace Corps volunteers. Some developing countries, understanding that their food protein scarcity will not be solved through animal proteins alone, are interested in growing the protein-rich peanut crop.

Where To Learn More

Books

Coyle, L. Patrick, Jr. The World Encyclopedia of Food. Facts on File, 1982.

Erlbach, Arlene. Peanut Butter. Lemer Publications, 1993.

Lapedes, Daniel, ed. McGraw Hill Encyclopedia of Food, 4th ed: Agriculture and Nutrition. McGraw-Hill, 1977.

Woodroof, Jasper Guy, ed. Peanuts: Production, Processing, Products. Avi Publishing Company, 1983.

Zisman, Honey. The Great American Peanut Butter Book: A Book of Recipes, Facts, Figures, and Fun. St. Martin’s Press, 1985.

Periodicals

“The Nuttiest Peanut Butter.” Consumer Reports. September, 1990, p. 588.

“PBTV.” Environment. November, 1987, p. 23.