Background

Wine is an alcoholic beverage produced through the partial or total fermentation of grapes. Other fruits and plants, such as berries, apples, cherries, dandelions, elderberries, palm, and rice can also be fermented.

Grapes belong to the botanical family vitaceae, of which there are many species. The species that are most widely used in wine production are Vit is labrusca and, especially, Vit is vinifera, which has long been the most widely used wine grape throughout the world.

The theory that wine was discovered by accident is most likely correct because wine grapes contain all the necessary ingredients for wine, including pulp, juice, and seeds that possess all the acids, sugars, tannins, minerals, and vitamins that are found in wine. As a natural process, the frosty-looking skin of the grape, called “bloom,” catches the airborne yeast and enzymes that ferment the juice of the grape into wine.

The cultivation of wine grapes for the production of wine is called “viticulture.” Harvested during the fall, wine grapes may range in color from pale yellow to hearty green to ruby red. Wine can be made in the home and in small-, medium- or large-sized wineries by using similar methods. Wine is made in a variety of flavors, with varying degrees of sweetness or dryness as well as alcoholic strength and quality. Generally, the strength, color, and flavor of the wine are controlled during the fermentation process.

Wine is characterized by color: white, pink or rose, and red, and it can range in alcohol content from 10 percent to 14 percent. Wine types can be divided into four broad categories: table wines, sparkling wines, fortified wines, and aromatic wines. Table wines include a range of red, white, and rose wines; sparkling wines include champagne and other “bubbly” wines; aromatic wines contain fruits, plants, and flowers; and fortified wines are table wines with brandy or other alcohol added.

The name of a wine almost invariably is derived from one of three sources: the name of the principal grape from which it was made, the geographical area from which it comes, or—in the case of the traditionally finest wines—from a particular vineyard or parcel of soil. The year in which a wine is made is only printed on bottles that have aged for two or more years; those aged less are not considered worthy of a date. Wine years are known as “vintages” or “vintage years.” While certain wines are considered good or bad depending on the year they were produced, this can vary by locality.

In general, red wines are supposed to age from seven to ten years before being sold. Because white and rose wines are not enhanced by additional ageing, they are usually aged from only one to four years before being sold. And, since the quality of wine can depend on proper ageing, older wines are generally more expensive than younger ones. Other factors, however, can affect the quality of wine, and proper ageing does not always ensure quality. Other factors affecting quality include the grapes themselves, when the grapes are picked, proper care of the grapes, the fermentation process, as well as other aspects of wine production.

Most wineries bottle wine in different size bottles and have different product and graphic designs on their labels. The most common bottle sizes are the half bottle, the imperial pint, the standard bottle, and the gallon bottle or jug. Most red and rose wine bottles are colored to keep light from ageing the wine further after they are on the market. While viticulture has remained much the same for centuries, new technology has helped increase the output and variety of wine.

(Vineyardists inspect sample clusters of wine grapes with a refractometer to determine if the grapes are ready to be picked. The refractometer is a small, hand-held device that allows the vineyardist to accurately check the amount of sugar in the grapes. If the grapes are ready for picking, a mechanical harvester gathers and funnels the grapes into a field hopper, or mobile storage container. Some mechanical harvesters have grape crushers mounted on the machinery, allowing vineyard workers to gather grapes and press them at the same time. The result is that vineyards can deliver newly crushed grapes, called must, to wineries, eliminating the need for crushing at the winery.)

History

Well documented in numerous Biblical references, evidence of wine can be traced back to Egypt as far as 5,000 B.C. Tomb wall paintings showing the use of wine as well as actual wine jars found in Egyptian tombs provide evidence of this fact. Because more northern climates and soil produce better wine, the growth of the wine industry can be traced from its emergence along the Nile River in Egypt and Persia northward into Europe and, eventually, to North America.

Though the wines of old were coarse and hard and had to be mixed with water, ancient Greek wine proved to be somewhat better than Egyptian wine. For this reason, Egyptians began importing it. Then Roman wines (from what would emerge to be Italy, Spain, and France) became notably superior. Eventually, French and German wines grew to be the most desirable, thereby shifting the center of wine production from the Mediterranean to central Europe. Some of the best wine in the world is still produced in southern France, particularly in the Bordeaux region, where wine has been made for more than 2,000 years.

The colonists brought wine production to the east coast of the New World by the mid- 1600s. The earliest account of wine used in the New World may be when the Pilgrims fermented grapes to celebrate their first Thanksgiving in 1623. Settlers tried to grow imported grape cuttings they brought from Europe, but unfortunately the European cut-tings had not developed immunities to the North American plant diseases that eventually killed them. By the middle of the nineteenth century (using the fruits of the abundant native Vitis labrusca grape plants) wineries were established in Pennsylvania, Virginia, Ohio, Indiana, Alabama, Mississippi, and North Carolina.

In 1697, European cuttings of Vitis vinifera grapes were successfully introduced to California by Franciscan priests at the Mission San Francisco Xavier. They soon became the dominant grape species in California wine making. A great boost to California wine making came from Colonel Agoston Haraszthy, a Hungarian nobleman, who introduced more high-quality European cuttings during the 1850s. His knowledge made him the founder of California’s modem wine industry.

Today, California and New York state are by far the largest American producers of wine, and California is one of the largest wine producers in the world. Though many of its table wines are known for their quality, the enormous wineries of central and southern California produce gigantic quantities of neutral, bulk wines that they ship elsewhere to make specific wines, such as dessert wines, or to blend with other wines. They also make grape concentrates to fortify weaker wines and brandies that use large quantities of grapes.

Raw Materials

As mentioned above, the wine grape itself contains all the necessary ingredients for wine: pulp, juice, sugars, acids, tannins, and minerals. However, some manufacturers add yeast to increase strength and cane or beet sugar to increase alcoholic content. During fermentation, winemakers also usually add sulfur dioxide to control the growth of wild yeasts.

The Manufacturing Process

The process of wine production has remained much the same throughout the ages, but new sophisticated machinery and technology have helped streamline and increase the output of wine. Whether such advances have enhanced the quality of wine is, however, a subject of debate. These advances include a variety of mechanical harvesters, grape crushers, temperature-controlled tanks, and centrifuges.

The procedures involved in creating wine are often times dictated by the grape and the amount and type of wine being produced. Recipes for certain types of wine require the winemaker (the vintner) to monitor and regulate the amount of yeast, the fermentation process, and other steps of the process. While the manufacturing process is highly automated in medium- to large-sized wineries, small wineries still use hand operated presses and store wine in musty wine cellars.

A universal factor in the production of fine wine is timing. This includes picking grapes at the right time, removing the must at the right time, monitoring and regulating fermentation, and storing the wine long enough. The wine-making process can be divided into four distinct steps: harvesting and crushing grapes; fermenting must; ageing the wine; and packaging.

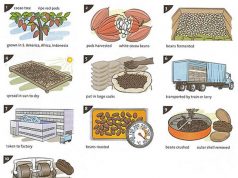

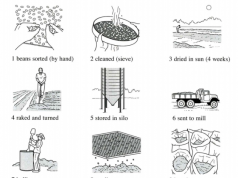

Harvesting and crushing grapes

1 Vineyardists inspect sample clusters of wine grapes with a refractometer to determine if the grapes are ready to be picked. The refractometer is a small, hand-held device (the size of a miniature telescope) that allows the vineyardist to accurately check the amount of sugar in the grapes.

2 If the grapes are ready for picking, a mechanical harvester (usually a suction picker) gathers and funnels the grapes into a field hopper, or mobile storage container. Some mechanical harvesters have grape crashers mounted on the machinery, allowing vineyard workers to gather grapes and press them at the same time. The result is that vineyards can deliver newly crushed grapes, called must, to wineries, eliminating the need for crashing at the winery. This also prevents oxidization of the juice through tears or splits in the grapes’ skins.

Mechanical harvesters, or, in some cases, robots, are now used in most medium to large vineyards, thereby eliminating the need for hand-picking. First used in California vineyards in 1968, mechanical harvesters have significantly decreased the time it takes to gather grapes. The harvesters have also allowed grapes to be gathered at night when they are cool, fresh, and ripe.

3 The field hoppers are transported to the winery where they are unloaded into a crusher-stemmer machine. Some crusher- stemmer machines are hydraulic while others are driven by air pressure. The grapes are crushed and the stems are removed, leaving liquid must that flows either into a stainless steel fermentation tank or a wooden vat (for fine wines).

(Once at the winery, the grapes are crushed if necessary, and the must is fermented, settled, clarified, and filtered. After filtering, the wine is aged in stainless steel tanks or wooden vats. White and rose wines may age for a year to four years, or far less than a year. Red wines may age for seven to ten years. Most large wineries age their wine in large temperature-controlled stainless steel tanks that are above ground, while smaller wineries may still store their wine in wooden barrels in damp wine cellars)

Fermenting the must

4 For white wine, all the grape skins are separated from the “must” by filters or centrifuges before the must undergoes fermentation. For red wine, the whole crushed grape, including the skin, goes into the fermentation tank or vat. (The pigment in the grape skins give red wine its color. The amount of time the skins are left in the tank or vat determines how dark or light the color will be. For rose, the skins only stay in the tank or vat for a short time before they are filtered out.)

5 During the fermentation process, wild yeast are fed into the tank or vat to turn the sugar in the must into alcohol. To add strength, varying degrees of yeast may be added. In addition, cane or beet sugar may be added to increase the alcoholic content. Adding sugar is call chaptalization. Usually chaptalization is done because the grapes have not received enough sun prior to harvesting. The winemaker will use a handheld hydrometer to measure the sugar content in the tank or vat. The wine must ferments in the tank or vat for approximately seven to fourteen days, depending on the type of wine being produced.

Ageing the wine

6 After crushing and fermentation, wine needs to be stored, filtered, and properly aged. In some instances, the wine must also be blended with other alcohol. Many wineries still store wine in damp, subterranean wine cellars to keep the wine cool, but larger wineries now store wine above ground in epoxylined and stainless steel tanks. The tanks are temperature-controlled by water that circulates inside the lining of the tank shell. Other similar tanks are used instead of the old redwood and concrete vats when wine is temporarily stored during the settling process. After fermentation, certain wines (mainly red wine) will be crushed again and pumped into another fermentation tank where the wine will ferment again for approximately three to seven days. This is done not only to extend the wine’s shelf life but also to ensure clarity and color stability.

The wine is then pumped into settling (“racking”) tanks or vats. The wine will remain in the tank for one to two months. Typically, racking is done at 50 to 60 degrees Fahrenheit (10 to 16 degrees Celsius) for red wine, and 32 degrees Fahrenheit (0 degrees Celsius) for white wine.

7 After the initial settling (racking) process, certain wines are pumped into another settling tank or vat where the wine remains for another two to three months. During settling the weighty unwanted debris (remaining stem pieces, etc.) settle to the bottom of the tank and are eliminated when the wine is pumped into another tank. The settling process creates smoother wine. Additional settling may be necessary for certain wines.

8 After the settling process, the wine passes through a number of filters or centrifuges where the wine is stored at low temperatures or where clarifying substances trickle through the wine.

9 After various filtering processes, the wine is aged in stainless steel tanks or wooden vats. White and rose wines may age for a year to four years, or far less than a year. Red wines may age for seven to ten years. Most large wineries age their wine in large temperature-controlled stainless steel tanks that are above ground, while smaller wineries may still store their wine in wooden barrels in damp wine cellars. The wine is then filtered one last time to remove unwanted sediment. The wine is now ready to be bottled, corked, sealed, crated, labeled, and shipped to distributors.

Packaging

Most medium- to large-sized wineries now use automated bottling machines, and most moderately priced and expensive wine bottles have corks made of a special oak. The corks are covered with a peel-off aluminum foil or plastic seal. Cheaper wines have an aluminum screw-off cap or plastic stopper. The corks and screw caps keep the air from spoiling the wine. Wine is usually shipped in wooden crates, though cheaper wines may be packaged in cardboard.

Quality Control

All facets of wine production must be carefully controlled to create a quality wine. Such variables as the speed with which harvested grapes are crushed; the temperature and timing during both fermentation and ageing; the percent of sugar and acid in the harvested grapes; and the amount of sulfur dioxide added during fermentation all have a tremendous impact on the quality of the finished wine.

Where To Learn More

Books

Adams, Leon. The Wines of America. McGraw Hill, 1978.

Anderson, Stanley F. Winemaking. Harcourt Brace & Company, 1989.

Churchill, Creighton. The World of Wines. Collier Books, 1980.

Farkas, J. The Technology & Biochemistry of Wine. Gordon & Breach Science Publishers, Inc., 1988.

Hazelton, Nika. American Wines. Grosset Good Life Books, 1976.

Johnson, Hugh. The Vintner’s Art: How Great Wines are Made. Simon & Schuster Trade, 1992.

McGee, Harold. On Food and Cooking. Collier Books, 1984.

Ough, Cornelius S. Winemaking Basics. Haworth Press, Inc., 1992.

Rainbird, George. An Illustrated Guide to Wine. Harmony Books, 1983.

Zaneilli, Leo. Beer and Wine Making Ill¬ustrated Dictionary. A. S. Barnes & Company, 1978.

Periodicals

Asimov, Isaac. “The Legacy of Wine,” The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction. July, 1991, p. 81.

Merline, John W. “What’s in Wine? (Calling All Consumers),” Consumers’ Research Magazine. November 1986, p. 38.

Oliver, Laure. “Fermenting Wine the Natural Way,” The Wine Spectator. October 31, 1992, p. 9.

Robinson, Jancis. “Spreading the Gospel of Oak,” The Wine Spectator. August 31, 1991, p. 20.

Roby, Norm. “Getting Back to Nature,” The Wine Spectator. October 15, 1990, p. 22